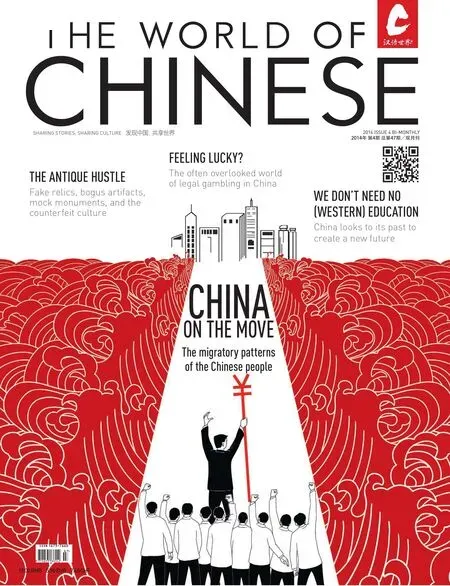

FEELING LUCKY?

2014-02-27BYCARLOSOTTERY

BY CARLOS OTTERY

FEELING LUCKY?

BY CARLOS OTTERY

A look into the oddities of legal gambling in China

中国人的“手气”汇聚起来,就支撑起庞大的博彩业

Go to any casino in the world and they are there by the bucket load, dozens upon dozens of seemingly inscrutable Chinese men sat behind ever increasing or decreasing stacks of chips, coolly throwing them down on whatever numbers feel lucky at the time. The stereotypical Chinese aff i nity for gambling is not exactly fi ction; it gave rise to a colossal, thriving three trillion RMB industry. Anytime, there is a national festival, communal gathering, or even funeral wake, the chance for a little low or high stakes gambling is taken: most often it's to the distinctive clack of plastic mahjong tiles that can be heard pretty much anywhere across the country; commonly, it is to any number of card games, from baccarat to cow-cow; sometimes it's on races between 100,000 dollar pigeons; and occasionally it's to something even more niche like cock-f i ghting, or odder still, to the fi ghting of tiny insects such ascrickets. In China, if a bet can be made, it will be made.

“Gambling is illegal in China” is something you hear a lot. You can hear tales of how Chairman Mao came to power and immediately banned anything and everything that was decadent and Western, from books and dancing right through to prostitution and, of course, gambling. But the well-trod notion that gambling in China is illegal is not quite true. There is, in fact, a successful 300 billion RMB industry that is completely legal and even administered by the government, except they don't call it gambling; instead a variety of euphemisms are employed, such as “colorful tickets” (彩票) or—on occasion and somewhat amusingly—“competitive guessing” (博彩). The China Welfare Lottery (中国福利彩票) and the China Sports Lottery (中国体育彩票) started in 1987 and 1989 respectively, and both allow Chinese punters to gamble on a number of different games including national and provincial lotteries, quick draw bingo type games, as well as scratch cards, and even sports. The lotteries are big news and due to a series of innovations, they have been growing by anywhere between 25 and 35 percent a year since their inception.

One rainy night, my friend Paul from Hebei and I visit a China Sports Lottery “bookies” for a bit of a fl utter in Beijing's Xizhimen area. On the way to the betting shop, Paul, who thinks such betting is pointless, gives me his views on the Chinese lotteries. “They are just a way for the government to steal money from the poor who want to make a lot of money fast. No rich guys would play these games. It's a waste of time,” he says. The betting shop in many ways echoes a British bookie from 20 years ago, albeit a very low rent version. Thick plumes of cigarette smoke hang in the air and empty beer bottles are dotted around the shop. A gaggle of middle-aged Chinese men sit huddled in the corner. They are studying a complex grid on a whiteboard where the numbers for the last few weeks' lotteries have been hastily jotted down. On the board, a line is drawn through the numbers and it seems to form a zigzag pattern, as it almost inevitably would. If you didn't give it much thought you could mistakenly think these zigzags form an identif i able and predictable pattern, and many of the men in the shop have methods and techniques for calculating the numbers. As Paul says, “These guys think they are working for the numbers. If they win they think it is because they deserved it.” It's all bunkum, of course; the numbers are completely random and therefore unpredictable.

The shop is run by a woman in her late 30s and her son, who was apparently helping out. Though the boy looks about eight years old, Mike Wang is actually 13. His family moved to Beijing from Shanxi to run the betting shop. They get a set wage, and if they sell over a certain amount they get a healthy commission. Mike's father was a welder, and his mother worked in insurance and sold Amway products on the side, but they thought they would have a better chance running a betting shop in Beijing. That was eight years ago, and the shop seems to be fl ourishing. Though just 13 years old, Mike, wearing a pair of bright yellow Nike football boots, seems intelligent and tells me it is his ambition to be an elite soldier. Very familiar with the betting shop itself, he eagerly helps me score my lottery slip and shows me how to play the game. For the draw, there are 33 numbers and a bonus ball, so I have to pick six numbers and a bonus and then hope they come up.

It's 2 RMB a go and I decide to buy fi ve lines to increase my chances. On rollover weeks, where nobody has picked the numbers in the previous week, the prizes can be fantastically huge. If the lottery rolls over for several weeks, the amounts can go up to hundreds and hundreds of millions of RMB. Mike helps me pick some of the numbers, seemingly at random, and I ask him if he thinks the numbers are predictable.“Who knows? It is impossible to tell,” he says. “We get two main types of guys in here. Some, like you guys, just quickly pick the numbers. The other guys think they can work out what numbers are going to come up and take longer picking the numbers. But they all seem to win the same amount as each other.”

THICK PLUMES OF CIGARETTE SMOKE HANG IN THE AIR AND EMPTY BEER BOTTLES ARE DOTTED AROUND THE SHOP

It turns out the draw for the lottery is not until the next day, so we buy a few instant scratch cards to see if we can win there and then. The scratchcards themselves have colorful names such as, “Digging the Golden Beans”,“Winning the Sky Battle”, “Unlimited 7 Fun”, and “Ten Times Good Luck”. The cards are fi ve or 10 RMB a piece. Each game feels slightly different, but they, of course, are not. In some, you have to get a set of arrows pointing in the same direction, others you need three lines of fruit in a row, and with some you need matching types of sky rockets to win. They are fun to play and there is a distinct adrenaline rush as you manically scratch the silver covering off the symbols underneath.

A betting shop staff member meticulously marks down winning numbers; experienced gamblers believe they can see patterns in this perfectly legal, government-sanctioned form of gambling

“THEY [CHINESE GAMBLERS] ARE MORE SERIOUS. SOME STUDIES FIND THAT CHINESE CASINO—GOERS GAMBLE MORE AS A FORM OF INVESTMENT.”

Suddenly Paul screams, “Dude, I just won 10 bucks.” Though the ticket itself actually cost 10 RMB, it feels like a victory of sorts and we go on to buy several more tickets. For someone who thinks gambling is a waste of his time, Paul enjoyed buying the tickets and orders more and more. The shop is full so we furiously scratch the cards outside, but Mike is on hand and only too happy to ferry our tickets and money to and from the shop as he explains how each game works. I spend 100 RMB on tickets, but “win” about 50 RMB on cards themselves. Mike tells me that the payout is about 65 percent on the scratch cards, so I'm well under the win average. This thought alone makes me think it is worth buying more.

Why the Chinese have a particular penchant for gambling is unclear, though betting can be traced back to at least the Zhou Dynasty (1046 BCE-256 BCE), possibly earlier, where there are records ofliubo(六博), a game of chance, as wellas cock fi ghting and horse racing. The nation is deeply steeped in its Confucian culture, yet Confucius himself didn't have much positive to say about the pastime, seeing gambling as wasteful, a moral ill, and something that could lead to social disorder. Professor Desmond Lam of the University of Macau has written extensively about Chinese gambling, “They [Chinese gamblers] are more serious. Some studies fi nd that Chinese casino-goers gamble more as a form of investment. They also take high risk bets that are way above the minimum betting amount,” he says.“They do gamble much more and more avidly. It is diff i cult to explain this phenomenon in a sentence, but I would group the reasons into external, for example high income disparity, and low or negative real interest rates, versus internal, that is the high illusion of control, risk seeking, social norms, etc.”

Lam has written extensively about this “the illusion of control”, essentially it's the idea that people feel they can control the outcome of games (even those requiring no skill) in some way. Oddly, this “illusion of control” partly comes from the fact that many Chinese believe they have less, not more, control over their lives than Westerners. Chinese have what Lam calls a very high “external locus of control”, meaning that they believe lots of other factors outside of themselves have a big impact on their ultimate fate, and this external locus can be underpinned by numerous things such as superstition, luck, destiny, and folk beliefs. Accordingly, larges sets of rituals and bizarre beliefs are often developed to add to their luck, which they believe needs to be built up. This “luck” is then deployed at the gaming table. Such rituals can take myriad forms such as the wearing of red underwear, not touching a gambler's shoulders during gaming, avoiding monks and nuns, the blowing of cards, and even various feng shui elements, like not going through the doors of gaming establishments that face certain directions; perhaps the oddest edict of the bunch is that female gamblers are more likely to fi nd success when they are on their period.

Casual gamblers hope to get lucky in a crowded betting shop in Shanghai as they discuss their strategies

A man carefully chooses his numbers in one of China's many legal betting shops

“THE MAIN REASON IS TO REDIRECT THE WEALTH GAINED IN UNDERGROUND GAMBLING ACTIVITIES INTO LEGAL MEANS AND USE THE WEALTH TO BETTER THE LIVES OF THE SOCIETY AS A WHOLE”

Lam also believes there is a subtle difference in the way Chinese society perceives gambling as a whole, and he suggests that, where in the West casino gambling is seen as entertainment, many Chinese see it as a form of investment. Perceived differences are particularly strong with proble gamblers, “Many see ‘small bets' as okay, and it is fun to gamble during festive seasons like Chinese New Year. It is also common for adults to let kids play a few rounds. Sometimes, it is seen to be for goodluck,” says Lam. “A person who cannot control his or her gambling activities is recognized as someone who cannot control his or her own behavior. This person is considered a morally bad person but in the Western perspective this person is ‘mentally' sick…Most Chinese don't report their gambling problems because of face issues. Only the big cases (i.e. leading to the embezzlement of funds) get reported in Chinese media.”

There are some disagreements as to the motivations behind the Chinese government's involvement in gambling; and there have been tentative attempts to introduce wider legalized gambling such as horse racing or even casinos on the Chinese mainland, but so far none have ever gotten off the ground. Some argue that the establishment of lotteries is simply a way for corrupt off i cials and others to line their pockets, others see it is an effective way to raise money for good causes, but most commonly it seems to be believed that it is a way for the government to get a strong regulatory grip on what could otherwise easily become a widespread problem. Lam certainly takes this view: “I think legalizing gambling in China is a way to take gambling away from the underground and to manage illegal activities better. This is a common reason in many other countries too.” He adds, “The main reason is to redirect the wealth gained in underground gambling activities into legal means and use the wealth to better the lives of the society as a whole.” Although, he sees the lotteries as continuing to grow, he does not think legal gambling will extend beyond the lotteries in the short term:“It will take a while for this to happen. I don't see the possibility of legalizing casino gambling on the mainland any time soon. It will be hard to control the social ills if it happens, and I don't think the central government can effectively do so.”

One of the quirks of China's legal gambling system is that although it's strictly administered by China's Ministry of Finance and effectively a nationalized industry, the day to day running of its various games are all completely outsourced to third parties. The Beijing Sports Lottery for example, despite taking in vast sums of money, only has 13 permanent members of staff. These third parties aggressively seek capital in any way they can. All of this has led to the somewhat bizarre situation whereby you can effectively buy shares in China's national state lottery on the New York-based NASDAQ. Chinese Sports Lottery betting website 500. com has the largest market share online in China and launched an IPO in November 2013. The prospect of investing on a New York stock exchange in a Chinese state-run online gambling network was an odd one, but, to many, it also looked like too much of a winning bet to pass up, and sure enough it was. The IPO went off with a bang in and shares opened at 20 USD, barely four months later they peaked at a healthy 56 USD in March 2014—currently standing just shy of the 40 USD mark. The Chinese lottery, it seems, offers strong returns by any standard.

For a nation that loves to bet so much, the country's betting industry is in an odd space. Illegal or not, China's over 3,000 years of gambling history is not going to end anytime soon. Governments the world over are only too happy to deride any number of vices, yet simultaneously tax them to the nth degree to fi ll national coffers, and a little (or large) fl utter has long been part of that equation. With the casinos of Macau and the horse riding in Hong Kong, in time it will become clear if legal gambling on the Chinese mainland will extend beyond the, for now, narrow con fi nes of its welfare and sports lotteries. Although, with three trillion RMB at stake, who would bet against it? Gambling, in modern China at least, may have only just begun.