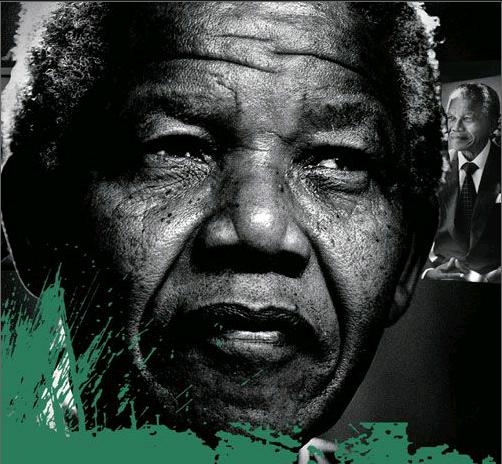

Nelson Mandela, 1918~2013: Remembering an Icon of Freedom纳尔逊·曼德拉:自由之魂

2014-02-27阿诺

阿诺

Nelson Mandela was always uncomfortable talking about his own death. But not because he was afraid or in doubt. He was uncomfortable because he understood that people wanted him to offer homilies2) about death and he had none to give. He was an utterly unsentimental man. I once asked him about his mortality while we were out walking one morning in the Transkei3) , the remote area of South Africa where he was born. He looked around at the green and tranquil landscape and said something about how he would be joining his “ancestors.” “Men come and men go,” he later said. “I have come and I will go when my time comes.” And he seemed satisfied by that. I never once heard him mention God or heaven or any kind of afterlife. Nelson Mandela believed in justice in this lifetime.

It was January 1993, and I was working with him on his autobiography. We had set out that morning from the home near Qunu, the village of his father, that Mandela had built after he was let out of prison. He had once said to me that every man should have a house in sight of4) where he was born. Much of Mandelas belief system came from his youth in the Xhosa5) tribe and being raised by a local Thembu King after his own father died. As a boy, he lived in a rondavel6)—a grass hut—with a dirt floor. He learned to be a shepherd. He fetched water from the spring. He excelled at stick fighting with the other boys. He sat at the feet of old men who told him stories of the brave African princes who ruled South Africa before the coming of the white man. The first time he shook the hand of a white man was when he went off to boarding school. Eventually, little Rolihlahla Mandela would become Nelson Mandela and get a proper Methodist7) education, but for all8) his worldliness and his legal training, much of his wisdom and common sense—and joy—came from what he had learned as a young boy in the Transkei.

Mandela might have been a more sentimental man if so much had not been taken away from him. His freedom. His ability to choose the path of his life. His eldest son. Two great-grandchildren. Nothing in his life was permanent except the oppression he and his people were under. And everything he might have had he sacrificed to achieve the freedom of his people. But all the crude jailers, tiny cells and bumptious9) white apartheid10) leaders could not take away his pride, his dignity and his sense of justice. Even when he had to strip and be hosed down when he first entered Robben Island11), he stood straight and did not complain. He refused to be intimidated in any circumstance. I remember interviewing Eddie Daniels, a 5-ft. 3-in. mixed-race freedom fighter who was in cell block B with Mandela on the island; Eddie recalled how anytime he felt demoralized12), he would just have to see the 6-ft. 2-in. Mandela walking tall through the courtyard and he would feel revived. Eddie wept as he told me how when he fell ill, Mandela—“Nelson Mandela, my leader!”—came into his cell and crouched down to wash out his pail13) of vomit and blood and excrement14).

I always thought that in a free and nonracial South Africa, Mandela would have been a small-town lawyer, content to be a local grandee15). This great, historic revolutionary was in many ways a natural conservative. He did not believe in change for changes sake. But one thing turned him into a revolutionary, and that was the pernicious16) system of racial oppression he experienced as a young man in Johannesburg. When people spat on him in buses, when shopkeepers turned him away, when whites treated him as if he could not read or write, that changed him irrevocably. For deep in his bones was a basic sense of fairness: he simply could not abide17) injustice. If he, Nelson Mandela, the son of a chief, tall, handsome and educated, could be treated as subhuman, then what about the millions who had nothing like his advantages? “That is not right,” he would sometimes say to me about something as mundane as a plane flights being canceled or as large as a world leaders policies, but that simple phrase—that is not right—underlay everything he did, everything he sacrificed for and everything he accomplished.

I saw him a handful of times over the past few years. He was much diminished. The extraordinary memory that could recall a particular dish at a dinner 60 years before was now such that he often did not recognize people he had known almost that long. But his pride and his regal18) bearing never left him. When he “retired from his retirement” (as he put it in 2004), I thought it was simply because he couldnt bear not remembering familiar things and he could not bear people seeing him in a way that did not live up to their expectations. He wanted people to see Nelson Mandela, and he was no longer the Nelson Mandela they wanted to see.

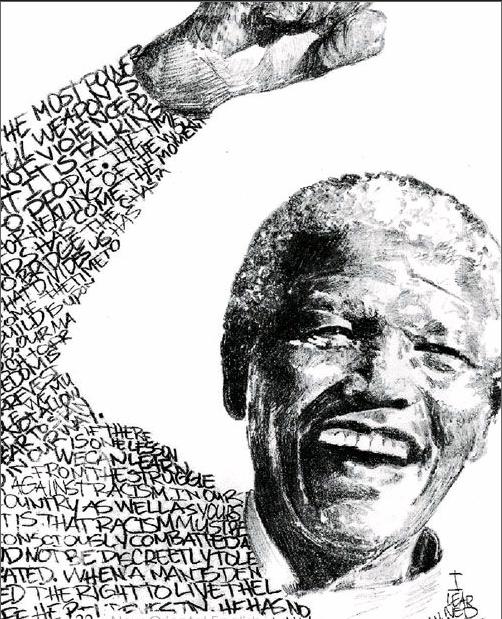

In many ways, the image of Nelson Mandela has become a kind of fairy tale: he is the last noble man, a figure of heroic achievement. Indeed, his life has followed the narrative of the archetypal19) hero, of great suffering followed by redemption. But as he said to me and to many others over the years, “I am not a saint.” And he wasnt. As a young revolutionary, he was fiery and rowdy20). He originally wanted to exclude Indians and communists from the freedom struggle. He was the founder of Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), the military wing of the African National Congress21), and was considered South Africas No. 1 terrorist in the 1950s. He admired Gandhi, who started his own freedom struggle in South Africa in the 1890s, but as he explained to me, he regarded nonviolence as a tactic, not a principle. If it was the most successful means to the freedom of his people, he would embrace it. If it was not, he would abandon it. And he did. But like Gandhi, like Lincoln, like Churchill, he was doggedly, obstinately22) right about one overarching23) thing, and he never lost sight of that.

Prison was the crucible24) that formed the Mandela we know. The man who went into prison in 1962 was hotheaded and easily stung. The man who walked out into the sunshine of the mall in Cape Town 27 years later was measured, even serene25). It was a hard-won moderation. In prison, he learned to control his anger. He had no choice. And he came to understand that if he was ever to achieve that free and nonracial South Africa of his dreams, he would have to come to terms with26) his oppressors. He would have to forgive them. After I asked him many times during our weeks and months of conversation what was different about the man who came out of prison compared with the man who went in, he finally sighed and then said simply, “I came out mature.”

His greatest achievement is surely the creation of a democratic, nonracial South Africa and preventing that beautiful country from falling into a terrible, bloody civil war. Several years after I finished working with him on Long Walk to Freedom, he told me that he wanted to write another book, about how close South Africa had been to a race war. I was with him when he got the news that black South African leader Chris Hani was assassinated, probably the closest the country came to going to war. He was preternaturally27) calm, and after making plans to go to Johannesburg to speak to the nation, he methodically28) finished eating his breakfast. To prevent that civil war, he had to use all the skills in his head and his heart: he had to demonstrate rocklike strength to the Afrikaner29) leaders with whom he was negotiating but also show that he was not out for revenge. And he had to show his people that he was not compromising with the enemy. This was an incredibly delicate line to walk—and from the outside, he seemed to do it with grace. But it took its toll30).

And because he was not a saint, he had his share of bitterness. He famously said, “The struggle is my life,” but his life was also a struggle. This man who loved children spent 27 years without holding a baby. Before he went to prison, he lived underground and was unable to be the father and the husband he wanted to be. I remember his telling me that when he was being pursued by thousands of police, he secretly went to tuck his son into bed. His son asked why he couldnt be with him every night, and Mandela told him that millions of other South African children needed him too. So many people have said to me over the years, “Its amazing that he was not bitter.” Ive always smiled at that. With enormous self-control, he learned to hide his bitterness.

And then, after he forged this new South Africa, won the first democratic election in the countrys history and began to redress the wrongs done to his people, he walked away from it. He became the rarest thing in African history, a one-term President who chose not to run for office again. Like George Washington, he understood that every step he made would be a template31) for others to follow. He could have been President for life, but he knew that for democracy to rule, he could not. Two democratic elections have followed his presidency, and if the men who have succeeded him have not been his equal, well, that too is democracy. He was a large man in every way. His legacy is that he expanded human freedom. He was tolerant of everything but intolerance. He deserves to rest in peace.

纳尔逊·曼德拉在谈到自己的死亡时总会感到不安,但这并不是因为他对死亡抱有恐惧或怀疑。他感到不安是因为他知道人们希望能从他那里听到关于死亡的教谕,而他却无以奉告。他完全不是一个多愁善感的人。一天早晨,当我们在他的出生地——南非边远的特兰斯凯地区一起外出散步的时候,我曾向他问起关于死亡的问题。他环顾着四周葱翠宁静的景色,谈到了自己将如何与“祖先们”相聚。“生命在世间来了又去,”他后来说,“我已来到这个世上,当我的大限到来时我就会离去。”对此他似乎感到心满意足。我一次都没有听他提起过上帝、天堂或任何有关来世的话。纳尔逊·曼德拉相信的是现世的公正。

那是1993年1月,我正在与他合作撰写他的自传。那天早上,我们从他位于库奴附近的家出发——库奴是他父亲生活过的村庄,出狱后他建起了这所房子。他有一次对我说,每个人都应该在看得到自己出生地的地方有一座房子。曼德拉的很多信念都来源于年少时在科萨部落的生活,以及在父亲过世后被当地的腾布王抚养长大的经历。小时候,他住的是圆顶茅草屋,脚下就是土地。他学会了放牧,会从泉中取水。男孩子们在一起用棍棒较量时,他是常胜将军。他曾坐在老人们的脚边,听他们讲在白人到来前统治着南非大地的英勇的非洲领袖的故事。他第一次和白人握手是在他离家去寄宿学校读书时。最终,小罗利赫拉赫拉·曼德拉会成为纳尔逊·曼德拉,会接受正统的基督教循道宗的教会教育;但尽管他修习过法律,也饱经世故,他的很多智慧和常识——以及快乐——都来自于童年时期在特兰斯凯所学到的一切。

如果不是因为人生中有太多的东西被夺走,曼德拉也许会是个更为感性的人。他失去了自由,也失去了选择自己人生道路的能力。他的长子和两个曾孙也先他而去。生活中恒定不变的只有他和同胞们所遭受的压迫。他牺牲了自己原本可以拥有的一切,投身到了为民众争取自由的事业中。但是,无论是粗暴的狱警、狭小的牢房,还是实行种族隔离政策的傲慢的白人统治者,都无法夺走他的傲骨、他的尊严和他的正义感。即使在初次进入罗本岛监狱时他被迫脱光衣服、任由狱警用水管冲洗他的身体,他依然站得笔直,没有叫苦。无论在任何情况下他都不会害怕。我还记得访问自由斗士埃迪·丹尼尔斯时的情景,这位身高五英尺三英寸的混血种人曾和曼德拉一起被关押在罗本岛监狱的B区。埃迪回忆说,每当他感觉意志消沉时,只要看到身高六英尺二英寸的曼德拉从监狱的院子里昂首走过,他就会再次充满斗志。埃迪流着泪向我讲述了在他生病时,曼德拉——“纳尔逊·曼德拉,我的领袖!”——如何来到他的牢房,蹲在地上为他清洗混杂着呕吐物、血和排泄物的脏桶。

我一直认为,如果南非是一个没有种族隔离的自由之地,曼德拉也许会成为一名小镇律师,满足于做一个地方上的显贵。这位具有历史意义的伟大革命者其实在很多方面是个天生的保守派。他不赞同为了改变而改变,但有一个原因促使他变成了一名革命者,那就是他年轻时在约翰内斯堡经历过的毒害社会的种族压迫制度。当别人在公车上向他吐口水,当商店店主拒绝他入内,当白人把他当文盲一样对待时,他被永远地改变了。因为他的骨子里有一种基本的公平感:他就是无法忍受不公。如果连他——纳尔逊·曼德拉,一位酋长的儿子,高大、英俊又有学问——都会被视为低人一等,那么成百上千万不具备他这样优越条件的人又会怎样呢?“那是不对的。”在谈论小到航班取消、大到某个世界级领袖制定的政策等话题时,他有时会这样对我说。而这句简短的话语——那是不对的——是他一切行动、一切牺牲和一切成就背后的原因。

在过去这几年,我见过他几次。他的身体状况已大不如前。他的记忆力曾经好到可以记起60年前某次晚餐中的一道菜,现在却经常连认识了近60年的人都认不出来。但是,他从未失去过自己的尊严和王者般的气度。当他“从退而不休的状态中彻底隐退”(他在2004年这样说过)时,我想那只是因为他无法忍受自己记不起原本熟悉的事物,无法忍受让人们看到一个有负众人期待的自己。他希望人们看到的是纳尔逊·曼德拉,而他已经不再是人们期望看到的那个纳尔逊·曼德拉了。

从许多方面来说,纳尔逊·曼德拉的形象已经成为了一种神话:他是世间最后一位高尚的人,是取得了英雄般壮举的人。的确,他的人生就像经典英雄故事里所描述的那样,在历尽苦难之后迎来了救赎。但正如他多年间对我和其他许多人所说,“我不是圣人”。他并非圣人。当他还是个年轻的革命者时,他脾气火爆、爱与人争吵。他起初曾想把印度人和共产党人排除在争取自由的斗争之外。他还创建了非洲人国民大会的军事组织“民族之矛”,并被视为20世纪50年代南非的头号恐怖分子。他钦佩在19世纪90年代的南非开展自由斗争的甘地,不过他向我解释说,他把非暴力运动看做一种策略,而非一项原则。如果这种策略是给南非人民带来自由的最好方式,他会欣然采用。如果不是,他会放弃。他确实这样做了。但就像甘地、林肯和丘吉尔一样,他在一件最重要的事情上始终顽固地坚守着正确的立场,并且从未忘记过这一点。

监狱这个熔炉塑造了我们所熟知的曼德拉。1962年入狱时,他是一个暴躁易怒的人。27年后,当他从监狱走出,走上阳光照耀的开普敦街头时,他已经变成了一个沉稳从容,甚至近乎安详的人。这样温和的态度来之不易。在狱中,他学会了控制怒火,因为他别无选择。他也开始明白,如果真的想把南非建成他梦想中那个自由而没有种族歧视的国家,他就必须与压迫自己的人达成和解,他就必须原谅他们。在长达数月的交谈中,我曾经多次问他,和入狱前相比,出狱后的他有什么变化。最后他叹息一声,然后简短地回答道:“出狱时我成熟了。”

他最重要的成就无疑是建立了一个民主的、没有种族偏见的新南非,并且阻止了这个美丽的国家陷入可怕、血腥的内战之中。在我结束与他合作《漫漫自由路》的几年之后,他告诉我说他想再写一本书,讲述南非曾经怎样处在种族战争一触即发的境地。当他得知南非黑人领袖克里斯·哈尼被刺杀的消息时,我就在他身边。那或许是南非最接近战争边缘的时刻。他表现得异常镇定,在做出前往约翰内斯堡向国民发表讲话的安排之后,他有条不紊地吃完了早餐。为了避免内战爆发,他不得不使出浑身解数:在与南非白人领袖谈判的过程中,他必须一边展现出磐石般的强硬,一边表明不会寻求报复的立场;同时,他必须向黑人同胞表明,他这样做不是在向敌人妥协。这件事处理起来需要如履薄冰——而在外人看来,他似乎应对裕如。但这个过程中仍然造成了一些伤亡。

因为他不是圣人,所以也会有凡人都有的痛苦。他曾说过一句名言:“斗争是我的生命。”而他的人生也是一场斗争。他爱孩子,却有27年的时间没有抱过孩子。在被捕入狱前,他过着地下工作者的生活,无法像他希望的那样尽到一个父亲和丈夫的职责。记得他曾经对我说过,当数以千计的警察追捕他时,他悄悄回到家中,照顾儿子上床睡觉。儿子问他为什么不能每晚都陪在他身边,曼德拉回答说,因为还有千百万个南非儿童同样需要他。这么多年以来,许多人对我说过:“他不觉得痛苦,真是了不起。”我总是报之以一笑。凭借着强大的自制力,他学会了把痛苦隐藏起来。

然后,就在他缔造了这个面貌一新的南非、赢得了南非历史上首次民主选举并开始着手纠正对黑人的不公正待遇之后,他选择了功成身退。只担任了一届总统就选择不再寻求连任,他成为非洲历史上绝无仅有的异类。和乔治·华盛顿一样,他知道自己迈出的每一步都会成为后来者效仿的榜样。他原本可以成为终身总统,但是他明白,为了建立起民主制度,他不能那么做。在他的总统任期结束之后,南非已经举行过两次民主选举。如果他的继任者没有他优秀,不管怎样,那也是民主。从各个方面来说,他都是一个了不起的人。他留下的遗产是他拓展了人类自由的疆界。除了褊狭的思想,他什么都可以宽容。他理应得以安息。

1. Richard Stengel:理查德·施滕格尔(1955~),美国记者、作家、编辑,曾任《时代周刊》(Time)总编辑,与曼德拉一起完成了曼德拉的自传《漫漫自由路》(Long Walk to Freedom)。

2. homily [?h?m?li] n. 说教,训诫

3. Transkei:特兰斯凯,南非东开普省的一个地区,也是种族隔离政策时期四个独立的黑人家园之一,1994年重返南非。

4. in sight of:在看得见……的地方

5. Xhosa [?k??s?] n. 科萨人(居住在南非开普省的牧民)

6. rondavel [r?n?dɑ?v(?)l] n. 有圆锥形房顶的圆形茅屋

7. Methodist [?meθ?d?st] adj. (基督教)循道宗的

8. for all:虽然,尽管

9. bumptious [?b?mp??s] adj. 自负的,傲慢的

10. apartheid [??pɑ?(r)t?he?t] n. (尤指南非当局对黑人及其他有色人种曾实行的)种族隔离(制)

11. Robben Island:罗本岛,位于南非西开普省桌湾中。1964年6月,曼德拉被当时的南非白人政府判处终身监禁,开始在罗本岛服刑,直至1982年才被转移到波尔斯穆尔监狱。

12. demoralize [d??m?r?la?z] vt. 使无斗志,削弱……的士气

13. pail [pe?l] n. 桶

14. excrement [?ekskr?m?nt] n. 排泄物,粪便

15. grandee [?ɡr?n?di?] n. 显贵,要人

16. pernicious [p?(r)?n???s] adj. 有害的,恶毒的

17. abide [??ba?d] vt. 屈从于,默默接受

18. regal [?ri?ɡ(?)l] adj. 帝王的,王者的

19. archetypal [?ɑ?(r)k??ta?p(?)l] adj. 典型的

20. rowdy [?ra?di] adj. 粗暴的,爱争吵的

21. African National Congress:南非非洲人国民大会,现为南非执政党,是南非最大的黑人民族主义政党,1960年被南非当局宣布为非法,1961年决定开展武装斗争,并成立“民族之矛”军事组织,由曼德拉任司令员。

22. obstinately [??bst?n?tli] adv. 固执地,顽固地

23. overarching [???v?r?ɑ?(r)t???] adj. 首要的,至关重要的

24. crucible [?kru?s?b(?)l] n. 熔炉;严峻的考验

25. serene [s??ri?n] adj. 平静的,安详的

26. come to terms with:与……达成协议

27. preternaturally [?pri?t?(r)?n?t?(?)r?li] adv. 异常地;不可思议地

28. methodically [m??θ?d?kli] adv. 有条不紊地

29. Afrikaner [??fr??kɑ?n?(r)] adj. 南非白人的

30. take its toll:造成损失(或伤亡等)

31. template [?tem?ple?t] n. 样板,模板