PRIMITIVE EXTREME

2014-02-25

PRIMITIVE EXTREME

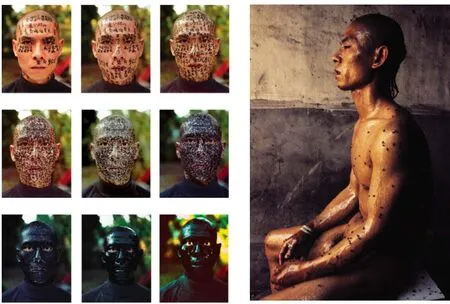

To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond, 1997

You were one of the first performance artists in China. How was performance art received in China at the time? How did people see the art form then, and how do they see it now?

I don't know. Critics have their own positions and understandings. I've never paid too much attention to this question. The works speak for themselves. My works ref l ect the conditions of my life at the time, conditions that were very common among the masses. It all seems like fate—the most important thing for an artist is that he uses his own standards to select objects, that he does that which is most interesting and most familiar to him. An artist must discover the signif i cance within everyday objects, transforming them into art using his own process. In my view, the artist's main task is to raise questions about art and about society, making works that represent the spirit of the times. This is the value of contemporary art.

Many of your works employ the body as an expressive tool. Why do you use your own (or other people's) body in your practice?

For a long time, I felt that there was an insurmountable distance between myself and the picture plane. One day, I found the lower half of a plastic mannequin in a garbage dump. There was one black leg, and it was hollow inside. I biked it back to my studio. It looked good, so I wore the mannequin's leg attached to my own. Just like that, I had three legs. It was a revelation—three legs! I tried to walk. It was very strange, but also exciting. It was as if I had discovered a method that was previously irresolvable. This method of body involvement totally astonished me. You could say that this was the fi rst time I used the body in an artwork in the truest sense of the phrase. The directness of using the body in art practice felt very grounding. I told myself that this was all I could do. Nothing else was necessary; nothing else moved me. I don't need anything. I only need my body.

Zhang Huan (张洹)

Zhang Huan is widely regarded as one of the most outstanding avant garde performing artists in China. Part of the artistic community known as the Beijing East Village, the now 49-year-old artist pioneered his particular brand of performance art in China in the 1990s. He believes his methods, often involving his own body as a means of expression, enable him to communicate directly with the world.

Family Tree (left), 2000 12 m2(right), 1994

You moved to America some years ago. After emigrating to America, did you fi nd that your work or your thought process had also changed?

My eight years in America were spent in a sort of tourist state, drifting, rootless. When I returned to China, my experience of tradition and belief was more profound. This experience is rooted in my everyday life. I discovered incense, door panels, leather…I was constantly having fl ashes of inspiration. Tradition is the body of a nation, and belief is its spirit. Body and spirit constitute a complete existence. China is now developing with all its might, but it cannot discard its body or its spirit. Returning to my mother culture, I felt that I was once again standing on solid ground, more deeply rooted.

It seems that there's been a shift in your works in the past 10 years or so, moving from your early performance and photography to large-scale installation and sculpture, like 2011's “Ask Confucius No. 6”. What was the inspiration for these new forms? Are there any themes that span your practice?

I'm only concerned about whether my works are, or are not, consistent with my internal life. I am inclined toward natural things, live things. Or rather, it's a very primitive…a primitive extreme, a sort of subversion. I fi rmly believe that I am changing, and that my works are changing. Artists must always stay fresh, must always make artworks that are fresh and live. One characteristic of contemporary art, as I understand, is that if it doesn't raise questions, then it loses its signif i cance. It is, in itself, inquisitive. It must raise its own viewpoint, one that is subversive. It can be narrative, but it must have its own position.

What artworks are you working on now? Are you preparing any exhibitions?

In April, Pace London will open my solo show “Spring Poppy Fields.” Audiences should fi nd my recent oil painting works a breath of fresh air. In May, New York's Storm King Art Center will hold the solo exhibition “Zhang Huan: Evoking Tradition” of many of my large-scale wrought copper and incense sculpture. After, I will also participate in the Gwangju Biennale in South Korea. - PATRICK RHINE