The Sabah Conflict: Grim Vision for ASEAN Security Community?

2013-12-11PaulPryce

Paul Pryce

Since the inception of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967, the member states have become increasingly interconnected and there has been correspondingly greater integration at the regional level.This process of integration has culminated in plans to form an ASEAN Community, encompassing economic,social, cultural, and security cooperation by 2015.But what ramifications might the recent instability in the Malaysian region of Sabah hold for these aspirations? What opportunities might the Sabah conflict hold for ASEAN as an emerging political and security community?

I.The Sabah Conflict

In February 2013, a long-standing but largely dormant territorial dispute over the Malaysian region of Sabah dramatically reignited.Armed rebels loyal to Jamalul Kiram III, a claimant to the traditional throne of the Sultanate of Sulu, occupied the village of Tanduo in Sabah in order to assert their claim to the territory.Malaysian security forces promptly surrounded the village.When attempts by both the Malaysian and Philippine governments to reach a peaceful solution with the Sultan’s supporters proved to be unsuccessful, the standoff escalated into armed conflict on 1 March 2013.

This conflict stems from a lack of clarity in an agreement signed by both the Sultanate of Sulu and the British North Borneo Company in 1878.Depending on the translation of this agreement, Sabah was either ceded or leased to the British North Borneo Company.The Malaysian government views the status of Sabah as a non-issue,understanding the 1878 agreement as one which ceded sovereignty from Sulu to the British and subsequently to Malaysia.The Malaysian claim to Sabah is further reinforced by a 1963 referendum, in which a majority of residents voted to join the Malaysian federation.

However, the Philippines and the descendants of the Sultanate of Sulu understand the 1878 agreement as a lease signed specifically with the British North Borneo Company and that the 1963 referendum was illegitimate.The Philippine position is strengthened by the actions of the Malaysian government itself: each year, the Malaysian Embassy in the Philippines issues a cheque in the amount of 1,710 US dollars to the legal counsel of the heirs of the Sultanate of Sulu.This would seem to suggest to some degree that there is an implicit understanding on the part of Malaysian authorities that Sabah was leased rather than ceded, even if the official Malaysian position is that these annual cheques constitute a “cession payment” and not a“lease payment” or a form of “rent”.

While the claim to Sabah remained dormant since the resumption of diplomatic ties between Malaysia and the Philippines in 1989,tensions began to emerge again in 2010.Apparently no longer satisfied with the payments made by the Malaysian Embassy, the claimants to the Sulu throne demanded that Malaysia drastically increase its annual payments to 1 billion US dollars.The Malaysian authorities ignored these demands and continued to issue annual payments of 1,710 US dollars.No further movement was made on the issue until 12 February 2013, when armed rebels from the Philippines professing loyalty to Jamalul Kiram III occupied the village of Tanduo.

The outbreak of violent conflict in Sabah is of some concern for the future of ASEAN as its member states seek further integration, even if the hostilities in Sabah can be characterized primarily as an intrastate conflict rather than an interstate conflict as the Philippines has not become military involved and has expressed no intent to do so.A treatment of these challenges for ASEAN as well as potential policy solutions will be addressed here.

The outbreak of violent conflict in Sabah is of some concern for the future of ASEAN as its member states seek further integration.

II.Challenges to the Formation of ASEAN Security Community

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which Malaysia and the Philippines are founding members, has emerged primarily as an economic organization, focusing much of its efforts on facilitating free trade among members and fostering economic growth.However, in the ASEAN Vision 2020 and the 2009-2015 Roadmap for an ASEAN Community adopted by the member states,ASEAN envisions establishing a fully functional political-security dimension by 2015.This envisioned ASEAN Political-Security Community would take on a role of central importance to Southeast Asia, functioning as a body for collective security and becoming the region’s mediator and adjudicator in any and all security disputes that might emerge among members.

This role for ASEAN may now be imperilled by the Sabah conflict, however.As of this writing, the Philippines and Malaysia have largely approached this conflict bilaterally, avoiding ASEAN as a potential forum for dialogue.ASEAN itself has also remained despondent in the midst of this crisis, with no collective action being taken or formal statements being made with regard to the Sabah conflict.The Malaysian press has taken particular note of ASEAN’s inaction and raised concerns that the Political-Security Community will be inoperable or at least ineffectual upon its official formation in 2015.1See for example: Deinla, Imelda.(2013, March 22).“ASEAN Non-Interference and the Sabah Conflict” The Malaysian Insider.Available at: http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/sideviews/article/asean-non-interference-and-the-sabah-conflict-imelda-deinla.

It must be noted that some of the foundations for ASEAN’s transition from a strictly economic community to a much broader security community have already been laid, reflected in the adoption of the Declaration on the Zone of Peace, Freedom, and Neutrality(ZOPFAN), the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in South East Asia(TAC), and the Treaty on the Southeast Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone (SEANWFZ).But a security community is greater than the sum of its institutions.Much research has been produced on the role of regional security complexes, a concept which holds that security interactions are often geographically structured and regionally focused.

Due to logistical issues and numerous other factors, security concerns can be exceedingly difficult to project over distances and security threats are more likely to form within a regional context rather than between remote corners of the globe.As such, many theories of international relations can be applied to specific regional security complexes and the patterns of interactions that emerge within these complexes, such as polarity or interdependence.

A security community is a specific kind of security complex where actors, according to Karl Deutsch, “settle their differences short of war”.1Deutsch, Karl.(1957).Political Community in the North Atlantic Area: International Organization in Light of Historical Experience.Princeton: Princeton University Press.If such a definition of a security community is to be accepted,then ASEAN already constitutes just such a community.Malaysia and the Philippines are not engaged in war over the status of Sabah as of this writing; the violence stemming from this territorial dispute has been solely between the Malaysian security forces and a non-state actor, the so-called ‘Royal Sulu Army’.But recent contributions to international relations theory hold that, more than eschewing war as a mechanism for settling disputes, security communities can be distinguished from other security complexes due to the prevalence of amity over enmity in the relations of the states which belong to that region.

In order to elaborate upon how these concepts of amity and enmity apply to ASEAN and to Malaysian-Filipino relations in particular, it will be necessary to put forward some definitions for these terms.Patterns of amity and enmity “…are socially constructed based on historical factors or common cultures.”2As such, among countries that share a common culture, amity will tend to prevail barring any exacerbating historical factors; the generally friendly relations of those states which enjoy membership in the Commonwealth of Nations or La Francophonie indicates how shared language can foster amity.

In short, amity predominates in a regional security complex when relations are positive, trust is high, and cooperation is close as a result of shared interests and perceived commonalities.Conversely,enmity predominates in a regional security complex when relations are strained, trust is low, and officials frequently express suspicion or even condemnation toward other states that share the same complex,whether this is a result of historical animosities, conflicting values,or simply clashing interests.Enmity need not necessarily result in war, but a security community necessarily requires amity and the high degree of trust in other actors that this reflects.If patterns of amity prevailed in Malaysian-Filipino relations, then the respective governments would have sought impartial mediation from an external party to resolve the dispute or the respective governments would have coordinated a security response to the conflict.This has not been the case.

This role for ASEAN may now be imperilled by the Sabah conflict.

Another exacerbating factor that challenges the formation of a security community in Southeast Asia is the lack of coherence in the region’s institutional framework.In other regions where the principles of a security community are present, integration is already high.To draw upon the European example, a kind of ‘security toolbox’ has been shaped by integrating processes over the course of decades, allowing European states to seek the peaceful resolution of disputes through the European Union, the Council of Europe,the Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe, as well as various other sub-regional bodies, such as the Council of Baltic Sea States or the now defunct Western European Union.With few exceptions, these institutions were not initially formed with a political-security dynamic in mind.

In some respects, the integration efforts envisioned in the 2009-2015 Roadmap and the ASEAN Vision 2020 come at a very late stage.Rather than pursuing the integration of the region concurrently in both the economic and security spheres, the norms of behaviour necessary for a security community to take hold could have been inspired by earlier economic integration efforts.That is to say, an ASEAN Community encompassing the economic and social spheres would have ideally come a decade prior to this recent push for an ASEAN Political-Security Community.

III.Ways to Advance ASEAN Security Community

Where amity among actors is inadequate for the existence of a security community, some measures can be employed in order to build trust.Some discussion has been held within ASEAN about the incorporation of such measures.With the recent outbreak of the Sabah conflict and the 2015 deadline for the establishment of an ASEAN Political-Security Community fast approaching, these discussions should take on a renewed sense of urgency and more ambitious proposals should be considered.At the heart of these previous discussions, as well as envisioned future talks, have been confidence and security building measures (CSBMs).

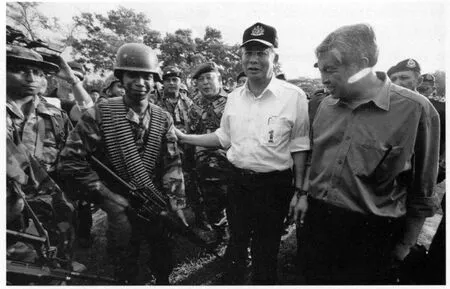

Malaysian security forces gunned down 31 Filipino intruders in Borneo on March 7,2013, the highest number of casualties in a single day since nearly 200 members of a Philippine Muslim clan took over an entire village last month.

CSBMs can take a variety of forms.These can range from information sharing and verification regarding military budgets and unit locations, military base inspections, invitations for neighbouring countries to observe military exercises and prior notification of said exercises, and even the designation of demilitarized zones in sensitive border areas.Many of these measures were pioneered in the 1999 Vienna Document, an agreement integral to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and to the current makeup of European security.

Person to person contacts have also emerged as an effective CSBM in a number of security communities around the world.These can include joint military exercises, exchanges between national militaries or other administrative bodies, and frequent meetings or conferences at various levels.For example, the Organization of American States, which counts all the countries of North and South America as its members minus Cuba, facilitates person to person contacts through its Inter-American Defence College and the Inter-American Defence Board.At a more grassroots level, it could also be said that the European Union’s Erasmus Programme is a CSBM carried out through people to people contacts, as it has allowed over 2.2 million post-secondary students to participate in study exchanges in countries other than that of their citizenship for durations of up to one year.

ASEAN already extensively employs person to person contacts as a CSBM.The ASEAN Summits, East Asian Summits, and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) are all forms of high level person to person contacts and can be understood as CSBMs for the ASEAN members themselves and for partners elsewhere in the international community with an interest in the affairs of Southeast Asia.But there are also grassroots elements of these person to person contacts in the region, mostly chiefly involving sports.The Southeast Asian Games,the ASEAN Para Games, the ASEAN Football Championship, and even the boxing championship which Malaysia boycotted in 2013 all constitute person to person contacts that can contribute to feelings of amity within a region.

In addition, the ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint adopted in 2009 envisions the development and publication of an annual ASEAN Security Outlook, which goes some way toward introducing a feature to ASEAN that is relevantly similar to the information exchanges held between defence and military officials in Europe under the auspices of the Conventional Forces in Europe(CFE) Treaty.A number of other CSBMs are also enumerated in the Blueprint, such as conducting joint research projects on defence issues and bilateral exchanges between defence institutions in ASEAN member states.

Finally, ASEAN also benefits from a series of aforementioned agreements in the area of defence and security cooperation.ZOPFAN, TAC, and SEANWFZ can all contribute toward mutual trust, confidence, and amity among the ASEAN member states.Yet this contribution is admittedly limited.The prospects of an ASEAN member acquiring nuclear weapons and threatening to use them against other members can be considered far-fetched as of this writing.Therefore, SEANWFZ can be considered a mostly symbolic gesture of security cooperation on the part of ASEAN member states; with the ‘Royal Army of Sulu’ waging a campaign of illegal occupation and insurgency in Sabah, it is doubtful that the Malaysian authorities consider the existence of a Nuclear Weapons Free Zone in Southeast Asia to be a reassuring or relevant security guarantee in Malaysia’s current relationship with the Philippines.

The ASEAN CSBMs discussed here are markedly softer than those outlined in the 1999 Vienna Document and practiced by the Soviet Union, the United States of America, and their respective European allies toward the end of the Cold War.Some scholars have attempted to attribute this reluctance to implement intensive CSBMs within the scope of ASEAN to the different historical and strategic contexts of Europe in the late 20th century and Southeast Asia in the early 21st century.Whereas Europe during the Cold War was suspended between two poles with considerable strategic and conventional arsenals, there is a relative absence of regional hegemons and ideological conflicts in modern Southeast Asia.Reflecting this reality, Satoh Yukio, a Japanese scholar, has proposed the adoption of‘mutual reassurance measures’ in the region.Paul Dibb, an Australian scholar, has proposed the alternative development of ‘trust building measures’ in ASEAN and elsewhere in the greater East Asian region.

What these trust building measures (TBMs) and mutual reassurance measures (MRMs) have in common is a softer and more gradual approach, a greater orientation toward grassroots efforts and exchanges, and a focus on bilateral relationships.At the outset, it can be seen that the implementation of TBMs or MRMs at the expense of CSBMs undermines the role of ASEAN.By placing emphasis on bilateral relationships rather than the regional community as a whole, the stated aim of transitioning ASEAN into a fully functional security community takes on secondary importance.This apparent side effect may not have factored into the considerations of Satoh or Dibb in their writings on TBMs and MRMs, given that their principal research focus was more so on the broader East Asian context.

But the proposal from some quarters that ASEAN should pursue TBMs or MRMs at the expense of CSBMs raises another important issue.As was previously mentioned, TBMs in particular, and MRMs to a lesser extent, tend to place greater emphasis on a gradual or incremental approach to building political trust between states rather than spectacular breakthroughs.But, in light of the recent conflict in Sabah and considering the tight timetable under which ASEAN expects to establish a Political-Security Community, what might be most needed now in the region is a ‘spectacular breakthrough’.If this is the case, then more ambitious CSBMs than the proposed ASEAN Security Outlook must be given due consideration by ASEAN member states.Rather than simply transplanting European regional practices though, there is an opportunity for ASEAN to adopt measures unique to Southeast Asia that would likely generate a great degree of amity among actors.

The base inspections allowed for under the 1999 Vienna Document and discussed here previously also have an exempting provision, namely the force majeure in Section 78 of that agreement.It refers to unavoidable and severely extenuating circumstances,such as war, internal strife, or natural disasters, due to which an inspection may be cancelled or delayed by the inspecting state or the receiving state.This provision obviously rules out the possibility of one OSCE member state sending a delegation to observe active military operations carried out by forces of another OSCE member state.The closest the OSCE comes to allowing for such observation is the deployment of military monitoring missions, which consist of unarmed military officers from a diverse array of OSCE members and which monitor demilitarized zones to ensure all parties to a conflict comply with any mutually agreed upon ceasefire provisions.For example, the OSCE had a military monitoring mission in Georgia until the expiry of the mission’s mandate in the midst of diplomatic deadlock at the end of 2008.

Residents of Tanjung Labian leave their village near where Filipino gunmen were locked down in a stand off in the surrounding villages of Tanduo in Sabah on March 10, 2013.

ASEAN could go further than the OSCE or perhaps any other security community in the world by allowing for bilateral observation.Under such a system, any member state conducting active military operations near the territory of another member state would be obliged to invite that other member state to observe the operations.This departs considerably from the European model of CSBMs in two important ways.First of all, the principle of force majeure is significantly compromised, since the invitation is extended in the midst of strife or even war.Secondly, the state conducting the operations is proactive in issuing the invitation instead of waiting for neighbouring states to issue requests of their own.

Had such a radical CSBM been in place prior to the outbreak of the Sabah conflict, this may have reduced tensions and ensured that amity continued to prevail in the relationship between Malaysia and the Philippines.Upon deploying security forces to surround the village of Tanduo, the Malaysian authorities would have alerted their counterparts in the Philippines to the situation and issued a formal invitation to send a delegation to observe the Malaysian operations.Regardless of whether the stand-off ended in a peaceful and diplomatic solution or the situation resulted in violence, this gesture may have bolstered confidence and mutual trust.Through the presence of the observing delegation, the Malaysian forces would have been pressured to take every precaution in avoiding the excessive use of force or repressive actions.At the same time, the Philippine government would have had no reason to issue a request for investigation on the part of Malaysian authorities.

Base inspections, information sharing, and the monitoring of military exercises are CSBMs that consistently generate amity.But when armed conflict does emerge in a region, drastic action is needed that can pre-empt potentially divisive speech acts on the part of relevant actors.In these situations, statements that advance the claim that, for example, Malaysian security forces may be carrying out a brutal crackdown against ethnic Filipino communities in Sabah generate enmity.Having a system already in place that allows for ASEAN and its member states to resort to desperate measures at desperate times - that is to say, the invitation for interested parties to observe active military operations - can avoid this sudden trend toward enmity and instead generate further amity.

The Sabah conflict may not be the only situation in which such a CSBM is necessary.If the Moro Islamic Liberation Front were to renew terrorist activities in the region of Mindanao, the Philippine military may need to engage in counter-insurgency operations.In order to alleviate any potential concerns that the Malaysian government may have with the movement of large numbers of Philippine military personnel and equipment so close to Malaysian shores, the Philippine government would be obligated under this envisioned CSBM to issue an invitation to their Malaysian counterparts to observe the operations.Given the complexities of the South China Sea, the lack of clarity in some state boundaries that came about as a consequence of the colonial legacy, as well as the presence of some intra-state conflicts, this CSBM could be employed in the future to assuage concerns stemming from any number of possible crises or clashes.

In light of all this, the ASEAN member states would be well served by revisiting the plans for an ASEAN Political-Security Community as soon as possible.Such discussions should be oriented toward strengthening the CSBMs envisioned for ASEAN, including the enumeration of provisions for the observation of active military operations.Going well beyond the precedents set by other regional security communities, this ambitious measure would send a strong signal both regionally and internationally that ASEAN is serious about establishing a fully functional security community where members not only avoid the use of warfare to pursue national interests but also share a high degree of mutual trust and affinity.Even if ASEAN member states were to stop short of this CSBM, a more comprehensive model for information sharing and verification than the ASEAN Security Outlook must be adopted for the Political-Security Community to succeed.This may require drafting, signing, and ratifying a new treaty, modelled on the CFE Treaty and complementing the ZOPFAN, TAC, and SEANWFZ.

Base inspections,information sharing, and the monitoring of military exercises are CSBMs that consistently generate amity.

IV.Conclusion

The actions of the rebel ‘Royal Army of Sulu’ constitute a threat to Malaysian sovereignty over the Sabah region, though reports suggest that the Malaysian security forces largely prevailed within the first days of open hostilities.It is vital to the long-term viability of the ASEAN Political-Security Community, however, that the challenges presented by the Sabah conflict not be quickly forgotten.A slight detour in the development of the 2009-2015 Roadmap for an ASEAN Community is clearly required.Though not currently on the agenda of the ASEAN, expanding upon the existing CSBMs in the 2009-2015 Roadmap would be prudent.

Committing to ambitious CSBMs will strengthen the emerging ASEAN Political-Security Community, avoiding potential embarrassment for ASEAN were the project to fail due to an apparent lack of commitment or due to growing distrust from one or more member states.Given the ambition of some of these proposals, such as the implementation of a formal and comprehensive information sharing and verification system, this may necessitate the adoption of a new treaty by all ASEAN member states.An excellent venue for these discussions would be the upcoming 22nd or 23rd ASEAN Summits in Brunei Darussalam in 2013.The Sabah conflict presents an opportunity for ASEAN member states to truly operationalize their envisioned security community through the adoption of strong CSBMs that are both home grown and draw inspiration from the experiences of other regions.Harnessing this opportunity will require decisive action on the part of the member states.

杂志排行

China International Studies的其它文章

- Managing Sino-U.S.Competitive Interdependence

- Building Towards a New-Type China-U.S.Relationship

- Seizing Opportunities and Overcoming Difficulties to Promote the Development of China-Africa Relations

- The “Middle Income Trap”:An Expanded Concept

- Asia-Pacific Regional Economic Cooperation and CJK Cooperation

- Does China’s Rise Pose a Threat to Russia?