Talk of the Township

2013-12-06YUANYUAN

Democratic consultations boost understanding between officials and locals in a coastal city

Renowned for its millennial celebrations in 2000,Wenling in Zhejiang Province is where the sun first meets China’s eastern coastline.The city is a bastion for private enterprises, which contribute to 90 percent of local economic growth.

What makes Wenling more famous than many other places in China with flourishing private economies is democratic consultation, a governance reform initiated in the late 1990s.Township authorities in Wenling have since organized dialogues with villagers’ representatives to discuss public policies.

Through democratic consultation, the administration is more transparent, and there are fewer misunderstandings or complaints in implementing policies, according to a China Central Television(CCTv) report last December.

“This is a way to encourage ordinary people to be involved in public policymaking.It conforms to the country’s efforts to improve its democracy,” Chen Yimin, Director of the Deliberative Democracy Office of the Wenling Committee of the Communist Party of China(CPC), told CCTv.

In his report to the 18th CPC National Congress last November, Hu Jintao, General Secretary of the 17th CPC Central Committee,said that socialist consultative democracy is an important form of people’s democracy in China.

“Extensive consultations should be carried out on major issues relating to economic and social development as well as spec ific problems involving the people’s immediate interests through organs of state power, committees of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, political parties, people’s organizations and other channels to solicit a wide range of opinions, pool wisdom of the people, increase consensus, and build up synergy,” Hu said.

Bright spots

In 1999, Zhu Congcai, then Secretary of the CPC Committee of Songmen Town in Wenling,was assigned to deliver a lecture on agricultural modernization. Considering that many such lectures often bore listeners, Zhu decided to make a change. Instead of preaching dry political theory, he proposed holding a consultation that would allow participating villagers to raise questions to officials.

Five days before the consultation, Zhu circulated a notice inviting villagers. More than twice his original estimate of 100 showed up to ask questions ranging from how the government used the previous year’s tax revenues to how the following year’s road construction was planned.

The consultation’s success exceeded expectations.“People were very active and brought up some very constructive suggestions as well,”Chen recalled.

Since then, Songmen has used democratic consultation in deciding on multiple public affairs. The Zhejiang Provincial Government sang high praises for the practice, and many neighboring towns later followed suit.

In April 2000, Muyu, another town in Wenling, held its first democratic consultation to discuss the construction of a park in the center of the town as part of a tourism promotion program.

villagers’ suggestions included building more pathways to the entrances and more entertainment facilities in the park. To the great surprise of local officials, some villagers with their late family members buried at the proposed site of the park voluntarily offered consent to have the tombs relocated.

“Without local residents’ support, it would have been almost impossible for us to move the tombs away,” Jin Xiaoyun, then Secretary of the CPC Muyu Committee, told Xiaoxiang Morning Herald, a newspaper published in Hunan Province.

The topic of Panlang Town’s first democratic consultation was to choose a location for constructing residential buildings. The original plan was rejected as it was too close to a factory and there are some differing ideas concerning architectural design.

People voted on the final decision. “No matter whether they are satis fied or not after the voting, they wouldn’t argue with officials because they were part of the decision-making process,” Chen said.

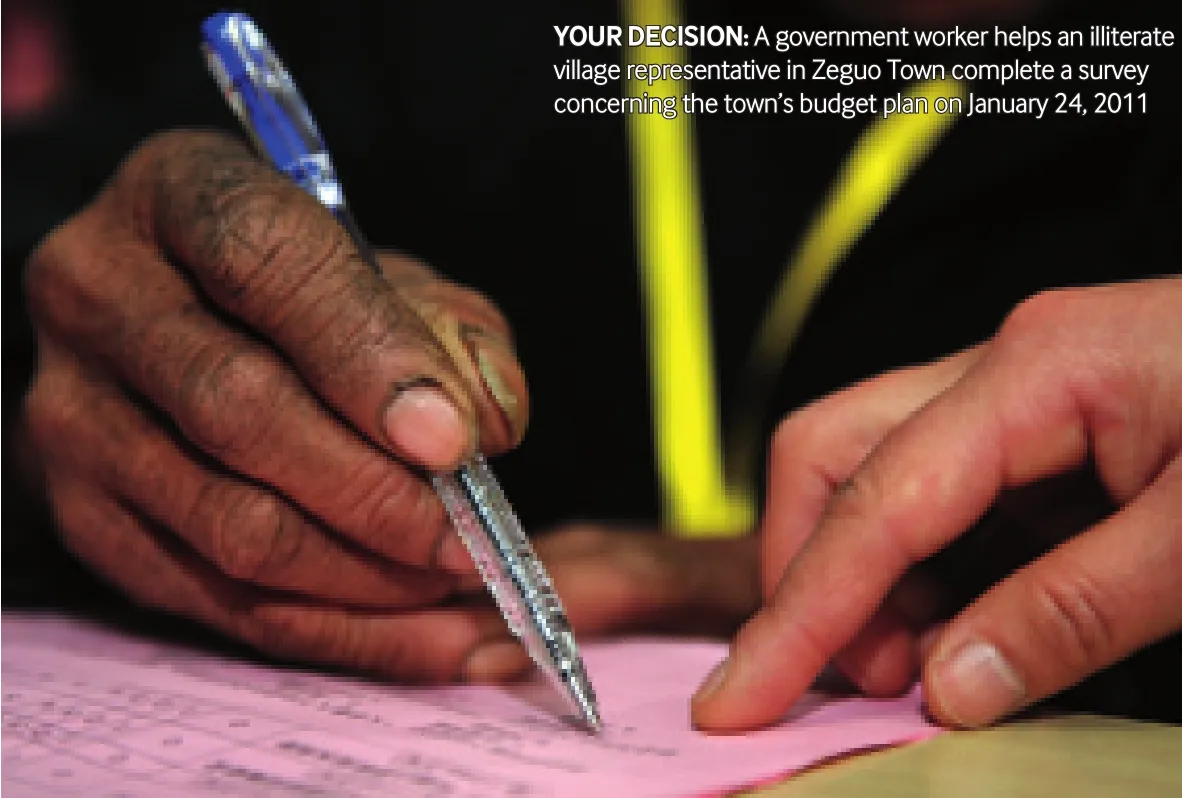

FREE EXPRESSION: villagers’representatives in Zeguo Town in Wenling, east China’s Zhejiang Province, engage in a heated discussion over the town’s budget plan on January 24, 2011

But in Songmen, the first to adopt democratic consultation, some village elders opposed the practice, saying that it would lower the efficiency of decisionmaking. Some villagers were blamed for wasting time with unconstructive haranguing of local officials.

Despite this, democratic consultation continued to take root in Wenling. People participating in such sessions gradually learned to determine very specific topics and to use this method to cover broader issues.

No mere expedient

In late 2001, implementation of democratic consultation became part of the criteria for evaluating Wenling officials’ performance.Governments of 11 towns in the city were required to hold at least four democratic consultations each year and make a clear report after each one.

“The support of town leaders is critical for the promotion of the reform,” Chen said. “In Xinhe and Zeguo towns, where democratic consultations have worked better, the support of the local governments plays a very important role.”

But Chen was still taking efforts finding a more consistent way to implement reforms in township governance. “If we can develop a complete set of rules for the reform, we could rely less on the officials,” Chen said.

In 2004, Chen met Li Fan, Director of the World and China Institute, an NGO studying China’s social and political changes after the adoption of reform and opening-up policies.Li had been studying Wenling for a while. He suggested Chen focus on democratic decisionmaking and introduce the democratic consultation mechanism to local people’s congresses.

According to Li, democratic consultation’s first priority should be deliberating government budget plans, a nominal responsibility of local people’s congresses. “In many township governments, the budget plan was made by local leaders alone,” Li said of his and Chen’s determination to enhance the role local people’s congresses play in formulating budgets.

Xinhe took the lead this time. The township people’s congress formed a special team of deputies to read and discuss the budget in detail in a meeting open to villagers.

“As it was the first open deliberation of a budget plan, nobody had any idea of how to proceed and everybody at the meeting seemed to be very nervous and kept silent,”said Jin Liangming, Secretary of the CPC Xinhe Committee. “The meeting didn’t bring out any different ideas on the plan.”

The budget plan was put aside until early 2006, when Ma Jun, a professor at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, southern Guangdong Province, went to Wenling and helped create a set of budgetary rules.

After that, assigned deputies deliberated on a draft of the budget provided by the local government, and reported the results of their deliberations to a full session of the Xinhe Town People’s Congress, which is charged with final approval of budgets.

Due to the success, deliberation of the 2006 budget plan of Xinhe turned out to be a lot more active and the participants raised many different ideas, including reducing the budget of a tourism facility construction project from 2 million yuan ($321,000) to 1.5 million yuan($241,000) and rejecting the purchase of a new car for a government official.

The final version of the 2006 budget plan for Xinhe Town was about 20 pages long, listing every item of expenditure in detail. “It was the longest budget plan in Wenling’s history,” Chen said.

Zeguo broke the record in February 2008,when its government drafted a 48-page budget plan. Zeguo also randomly picked 175 out of 120,000 local residents to join in the discussion and present their ideas. Zhao Min, Secretary of the CPC Zeguo Committee, revealed that officials spent more than a month collecting ideas from local residents before drafting the budget.

Chen said that the new procedure helped eliminate Xinhe’s budget deficit in 2010, which was 58 million yuan ($9.31 million) in 2004.

“Our next step is to monitor the execution of the budget plan,” Chen said. “The process will be open to everyone and relevant data will be published once every season.” ■