Ultimate Master of Mianzhu Woodblock Prints

2013-04-29BystaffreporterLIYUAN

By staff reporter LI YUAN

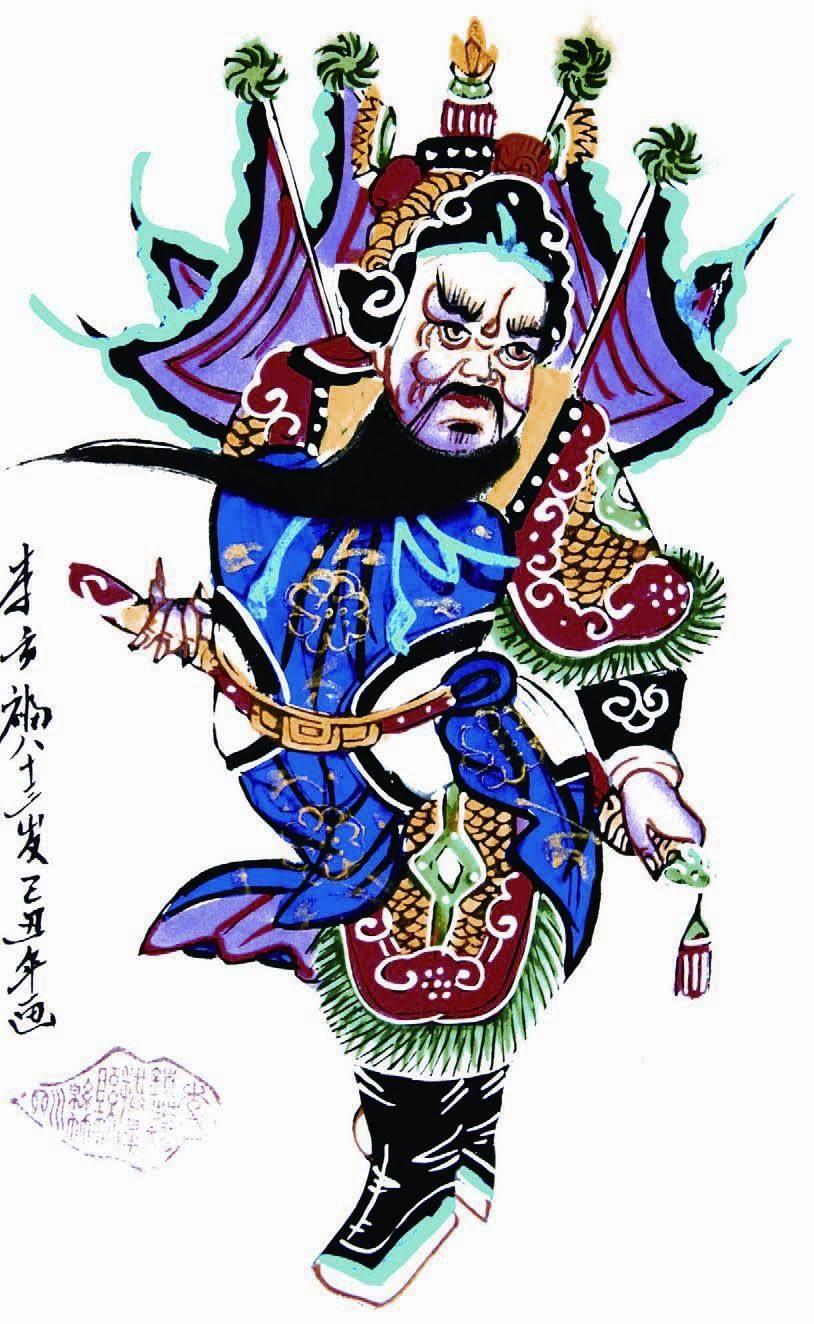

SOME say it was the Door gods that saved Li Fangfu and his studio in Mianzhu, Sichuan Province, from complete destruction in the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Last representative inheritor of the venerable Mianzhu woodblock printing craft, Li Fangfu, now 83, and his workers have honored for decades this everyday deity through the woodblock prints they produce in Lis studio.

Chen Xingcai, Li Fangfus fellow state-level inheritor of Mianzhu woodblock prints, having passed away last year, Li is the last exponent of the craft and sole bearer of this title.

Li was born in 1930 in Gongxing, a small town in Mianzhu County. At age 12 he was apprenticed to Master Huang Anfu of the northern school of woodblock printed art. Decades of dedication have made Li skilled in the sophisticated four-color printing techniques of the school and nurtured his distinctive style. Streams of domestic and international buyers specializing in this Chinese folk art come every year to see Li in his 10-square-meter studio on a nondescript alley and place orders for his works.

Li received official recognition of his lifetime achievements and contributions to Chinese New Year prints in 2006, when he was included among Chinas first batch of Inheritors of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Woodblock Prints as Intangible Cultural Heritage

Mianzhu woodblock prints became popular in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when Chinas printing industry thrived. They represent one of the four major schools of traditional Chinese New Year prints, the other three being those of Yangliuqing in Tianjin, Yangjiabu in Weifang, Shandong Province, and Taohuawu of Suzhou in Jiangsu Province. All four were included in the first batch of National Intangible Cultural Heritage.

In earlier times, papermaking was the main industry in Mianzhu. Workshops that lined the small river running through the town produced fine paper of high repute in the area. They laid foundations for Mianzhus flourishing woodblock printing trade.

Similar to the Western custom of hanging wreaths of holly on the front door at Christmastide, the Chinese tradition of decorating homes with New Year prints at Spring Festival, or Lunar New Year, goes back centuries. Ladies of the house decorate doors, windows, halls, inner chambers, the kitchen stove, and even water jars with colorful and auspicious New Year prints to herald the advent of spring.

The demand for Chinese New Year Prints has waxed and waned, revived and mutated, but they have long been acknowledged as quintessential Chinese folk art.

Along with Sichuan opera and cuisine, Mianzhu woodblock prints, with their accumulation of characteristically Sichuan-style folk New Year paintings, are instantly identifiable as a main aspect of the Bashu culture. Each starts with a sketch that is then drawn, outlined, printed and painted. It is the coloring process that distinguishes Mianzhu woodblock prints, because each piece of work is individually handpainted. It is hence fair to say that every Mianzhu woodblock print is unique.

Eighty-three and Kicking

Li loves his work and life in general. He and his wife live in an old rented house in downtown Mianzhu. Both their son and grandson are in Gongxing, Lis hometown, where they have opened a Mianzhu woodblock printing school and do a brisk trade in New Year prints.“Theyve got their business, and I have my life,” Li said.

Li gets up early each morning and works five to six hours a day. Doing what he loves obviously keeps him both mentally and physically fit.

Li believes that the quality of each print reflects the painters mental state. He hence prefers to execute this stage of the work only when his humor suits. He decided this year to stop wearing reading glasses to give his work a more spontaneous quality.

All the paintings on exhibit in Lis studio are his own works. Their compositions are rich and varied, featuring intricate patterns, bright, bold colors and smooth, graceful lines. They include pictures, as well as calligraphic horizontal scrolls and semantically auspicious, concisely worded Spring Festival couplets to be pasted on doors, windows, calendars and decorative screens. Thematic sources include Chinese operas, local customs, famous beauties, symbols to celebrate weddings and other happy events, flowers, and landscapes.

Li paints on locally produced paper made from bamboo that grows in Mianzhu. The fine layer of dirt from Maoxian County in which he coats each sheet enables it to absorb and retain rich and durable colors. The use of this locally produced paper was formerly a special feature of Mianzhu woodblock prints. Most local artists, however, later opted for rice paper, which is much easier to produce.

Lis works epitomize the Sichuan style. The image of the God of Wealth Marshal Zhao Gongming, believed to bring wealth to the household, is crude with exaggeratedly wide angry eyes. The boldly colored Door gods, who ward off evil spirits with their iron whips, symbolize vigorous masculinity. Noble ladies are also portrayed in the racy, vital Sichuan style that is in stark contrast to the mild, mellow approach that characterizes prints from southeast China.

Mianzhu woodblock prints stand out by virtue of the originality of the painting process. As Li explained, “Although printed from the same template, artists can nonetheless convey their own style through the painting process.” He pointed out the folds on the Door gods robe in one print, saying, “These werent on the template, but painted by hand, as were the mustache and eyebrows.”

Life and Times of a Woodblock Painting Master

Lis early years as apprentice woodblock printer were no picnic. Having lost both his parents, he took up the craft in a last-ditch attempt to earn a living and survive. As time passed he saw the wisdom of his mentors belief that every trade and profession produces its own masters, and put all his energy into perfecting his craft.

“Back then, apprentices had to join the Mianzhu Woodblock Printers Guild in a ceremony involving two tables symbolizing the mentoring relationship,” Li recalled.

Guild rules were strict. They forbade any shortcuts in the production process or the selling of fake prints. There was no interaction between the western and southern schools as each had its distinct style. Trade fair dates and procedures were fixed, the first day of the 10th lunar month being reserved for laying out samples for customers to consider, and the setting up of the stall to sell New Year prints strictly scheduled for the first day of the 12th lunar month.

The market flourished at that time. Held in a school on Nanhuagong Street, the hundreds of booths that comprised the trade fair stayed open through to the small hours. There was another, smaller fair on the road to Qingdao Township.

During the 1940s, Mianzhu woodblock prints were sold in southwest and northwest China, and also in Japan, India and Southeast Asian countries.

Li has devoted his whole life to woodblock prints and in that time witnessed Chinas social transformations. He can recall how, long ago, every family would plant vegetables and crops and create their own New Year paintings at Spring Festival. The cultural environment in Mianzhu was perfect for producing woodblock prints. But urbanization over the past three decades has changed life styles. When people moved out of their courtyard dwellings into residential buildings, the tradition of adorning homes with New Year prints gradually faded. They are no longer a Spring Festival staple, but rather a sought after and widely collected genre of art.

“When folk art departs from peoples life, it exists only as cultural heritage,” Li said.

Since the 1990s, Mianzhu woodblock prints have experienced a remarkable revival. Lis studio still receives countless visitors, researchers, and investigation groups from around the world.

Well-known Chinese writer and folk art researcher Feng Jicai first visited Lis studio in 2004. He later wrote a book on Chinese woodblock prints that included conversations with Li and the two other Mianzhu woodblock print experts, Chen Xingcai and Chen Xuezhang. After the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake struck, Feng returned to Mianzhu to see if Li and his studio had survived the disaster.

Lis biggest worry after the quake was whether or not the painting materials stored in his old house, comprising three decades worth of the costly powder to make Mao dirt, precious pigments in specific colors, and most of all the hundreds of pearwood engraved woodblocks that were his lifes work, had withstood the disaster.

Decades of persistence and dedication to Mianzhu woodblock prints have enriched Lis artistic experience. When he met with artists of the Taohuawu School who came to help rebuild Mianzhu after the earthquake, Li shared with them his technique of protecting engraved woodblocks with foaming mold rather than a bristle brush.

Li has always sought better ways of telling traditional stories in his paintings. One piece entitled Wang Xiang on Ice, celebrating the virtue of filial piety, tells of the boy Wang Xiang who used the warmth of his body to melt ice on the river to catch fish for his parents to eat. He realistically portrays Wang doubled up and shivering in agony rather than just laying passively on the ice as generally depicted.

Li believes that drawing with compassion according to keen observations of life and reflections on human deeds is the only way to create great artistic works. His portrait of a noble lady riding a bicycle originates in the women he sees on the street every day. “The people I see are my sources of inspiration,” Li said.

Li, his son and daughter compiled a colored edition of the classic Twentyfour Stories of Filial Piety. His intention was to educate children in Chinese traditional moral values. “Material gain was not the sole aim, because artists and craftspeople also have social responsibilities,” Li said.

As young people today leave Mianzhu to experience contemporary lifestyle in big cities, there are few potential inheritors of Mianzhu woodblock prints. None of the dozens of apprentices Li has taken on in recent years has stayed the course.

“Painting is about building inner strength,” Li said. “Young people these days are generally too restless and superficial to devote themselves heart and soul to it.”

So far, only Lis son and grandson have learned the essence of his painting techniques. Li presides over all kinds of activities and lectures related to Mianzhu woodblock prints. As he said, “Ive been painting for more than 70 years, and as long as I can still lift my paint brush Ill carry on.”His main hope is to create more works for future generations.

“Painting, like society, requires balance and harmony,” Li said when talking about the garments the Door god wears in one of his works. “The robe is mainly scarlet, but has glints of light green to balance the tone, and of gold, silver, black and white to brighten the whole picture. A harmonious social life is similarly achieved by the efforts of all the people it comprises.”