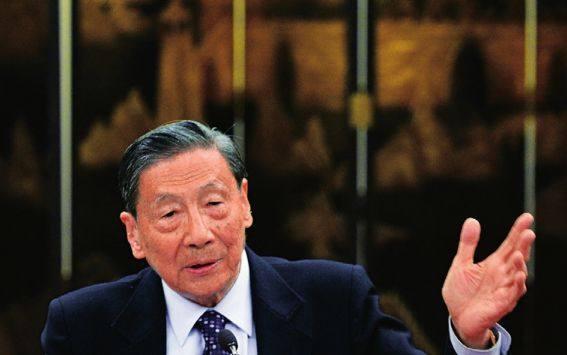

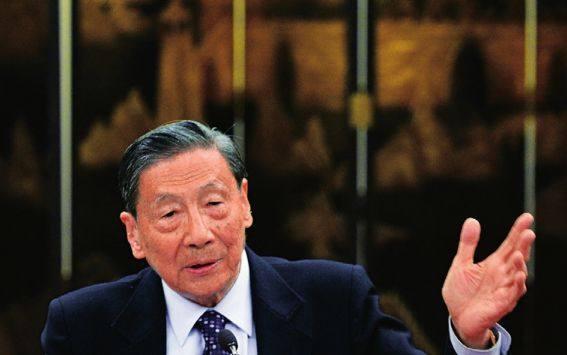

The Personalized Society and the Mao Yushi Phenomenon

2013-04-29

AS China opens up to the outside world like never before, the country itself is experiencing internal social change. One significant aspect of this is the rise of responsible individualism. Thanks to citizens who think independently and critically, but who nevertheless concern themselves with the public good and social development, civil society is developing in China.

China is changing rapidly; today, many maintain that internal happenings are taking the country towards a kind of “personalized society.” To understand this development is to understand contemporary China. A look at the “Mao Yushi Phenomenon”is a good start.

Social Conscience

Mao Yushi (no relation to Mao Zedong) is 82 years old. Currently he occupies the post of Director of the Unirule Institute of Economics, a renowned independent, non-governmental think tank.

In his professional capacity, Mao is not known to shy away from the sore points in modern Chinese history. For instance, he is on record as saying that the “cultural revolution” was a tragedy, and that the Mao Zedong era, while witnessing the development of a cohesive national consciousness, also saw extremes in ideology. The nation was hollow under the great chairman, Mao Yushi has written. It lacked independent thinking – there was no such thing as individual freedom – and the can-do spirit of liberalism was sadly absent. The nation was led to believe that to live in poverty was a kind of utopia, and self-reliance was seen as a way to “liberate all mankind.”

In his eclectic writings, again and again Mao Yushi has urged Chinese society to confront its own past and reevaluate the way it sees the “cultural revolution.” He says that only if the nation bids a final and collective farewell to that catastrophic era of extremes will it embrace a new era of unabashed, reform-driven modernity.

Why is Mao Yushi a phenomenon? What he writes is not sensational, nor is it counterfactual. Rather, the octogenarian has the ability to stir meaningful debate among the Chinese public in a way quite unlike any other public intellectual. In some respects, Mao Yushi has opened the floodgates to lively public discourse.

Mao Yushi is a patriot, mind you, but not in the narrow, take-no-prisoners sense of the word. In his writings and speeches he has never shied away from criticizing social trends or government policies that he perceives as running counter to the countrys healthy development. He has said that he will spare no efforts in his life to fight for “Chinas burgeoning middle class to have freedom of expression, and for the countrys poor to live comfortably.” Mao is a passionate supporter of the market economy. He writes that a booming market should be the way forward for China, and he criticizes the monopolistic behavior of the large state-owned enterprises. It is in the nature of the market economy to eliminate “privilege and monopoly” and to award power to the public, Mao contends.

Maos views are deeply rooted in the social conscience of 21st-century Chinese intellectuals. Besides his belief in the market economy, Maos philosophical system also advocates equal protection of all under the rule of law. Those who get by on low incomes should also have access to welfare, he argues.

Mao Yushi views political reform as important. He writes that this reform is happening, and that the countrys progress in democratic governance and the rule of law represents an ongoing achievement of reform and opening-up. The ruling Communist Party and other Chinese elites must finetune their approach to government in order to advance democratic progress throughout the state apparatus. Democratic government, Mao writes, is not only a key development indicator within China, but also marks the real rise of China in the world.

Mao nonetheless opposes mechanical imitation of Western political systems. China must create and follow its own path to modernization. He never moderates his argument that the electoral system popularly practiced in the West may not fit China. The future of Chinas political development will be bright only if that development is based on the historical and political traditions of the country. But at the same time, Mao writes it is important to learn from the West and study the worlds best-practice democratic political systems.

A leading intellectual in modern China, Mao is also comfortable discussing the classics. He has written, for instance, that the core meaning of the Confucian analects is learning. In the modern area, he continues, this includes learning from other countries in institutional innovation and economic development. He reiterates his view that a rising and growing China must be a country that is adept at learning from others.

Whats Behind the Controversy?

While Maos views, concerns and policy suggestions have in a sense become typical of engaged Chinese intellectuals nowadays, his essays are nonetheless controversial in the eyes of the Chinese public. Behind the public debate, however, is something encouraging: Chinese society is embracing a diversity of opinion. Its a harbinger of the new“personalized society.” Not everyone needs to agree to get along.

Thanks to many decades of reform and openingup, China is growing to be a society in which different views and values exist side by side. For instance, those critical of Mao Yushi are usually fans of the Mao Zedong era. For them the period is one of nostalgia, and once in which they could enjoy the“cradle-to-the-grave welfare system of a genuine socialist society.” In the eyes of such people, though life was hard owing to meager incomes and a lack of basic daily necessities, people were free from modern anxieties such as paying for housing, medical care and education. Furthermore, they say, income disparity was non-existent.

Another often-mentioned critique of Mao Yushis views is that the world nowadays is split into two ideological systems, West and non-West. China is firmly in the non-West camp – the “Oriental,” if you will, which differs from its Western counterpart in many ways. People who espouse these views see the two ideological systems as competitors: China should rise to contain, or even dominate, the West, they say. This line of thought, however, is based on a static understanding of history and takes the historical East-West dichotomy as immutable.

Ironically, the popularization of Mao Yushis work reveals just how out of touch his critics are. In many ways, in fact, Maos essays reflect reality. China is working with the international community more than ever before, and the majority of Chinese believe that partaking in globalization is an ideal opportunity to continue the nations rejuvenation. The path China is on right now is also affording the country the best of both worlds: the best aspects of its ancient civilization are being preserved, while at the same time the country is learning from Western experiences in democracy, the rule of law and technological innovation.

Chinese President Xi Jinping said on June 26 at a meeting attended by all the members of Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee that China should follow a development path of its own. But it could not ignore the big trends in world development, he emphasized.

The controversy behind the “Mao Yushi phenomenon” is natural. It is even to be expected in a country home to an increasingly diversified array of social and political thinking. Ideological debate should always be regarded as healthy, even vital to the development of a society mature enough to tolerate it.

The Society of Tomorrow

In the 35 years since reform and opening-up policies were inaugurated, arguably the most significant change in China has been the development of an “open society.” Along with greater tolerance for the expression of different opinions, openness has exposed the public to a wider range of thought than ever before, a must for the countrys positively contributing to world development. That Mao Yushi enjoys such wide renown is the result of social and political progress.

Currently, Chinas open society is growing into a personalized one. What does this mean at a tangible level? Individual Chinese citizens are now feeling it is their responsibility to further the countrys social progress.

A personalized society will foster a new political climate, which will require new political experiments. Luckily such experiments are nothing new in the country.