Progressive Justice

2012-10-14LiLi

Progressive Justice

The country’s first white paper on judicial reform s highlights the essential issue of protecting human rights By Li Li

I n May 2010, Zhao Zuohai, a farmer from Zhaolou Village, central China’s Henan Province, became a household name in China overnight. After languishing in jail for 11 years as a convicted murderer of a fellow villager, Zhao was declared innocent and released after his alleged victim returned home on April 30.

Later investigations showed that the w rongful conviction was largely based on Zhao’s own confession, which was extracted under torture by the police.

In May 1999, police investigators dug out a headless body from a well in Zhao’s village.They believed the man to be Zhao Zhenxiang,who had gone m issing in October 1997 after a fight w ith Zhao Zuohai over a woman they were both romantically linked to.

Zhao Zuohai had been tortured for 33 days before his confession. Five police officers were sentenced to jail for torturing him in 2012. Four days after Zhao Zuohai’s release, he received 650,000 yuan ($103,000) in state compensation.While his loss of freedom and absence from the lives of his four children for a decade cannot be compensated by money, the country’s top legislature has acted quickly to ensure that such a miscarriage of justice will never be repeated.

The Criminal Procedure Law amended in 2012 makes it clear that confessions by a suspect or a defendant obtained through extortion or other illegal means, and witness’ testimony and victim’s statements obtained through the use of violence, threats or other illegal means should be excluded from evidence.

The new ly amended law also clearly stipulates that no person may be forced to prove his or her own innocence, and no criminal suspects or defendants may be forced to confess.

China’s legislative improvements to prohibit the exacting of evidence through torture or other illegal means by judicial officials is on record in the country’s first government white paper on judicial reforms, which was issued on October 9.

Straigh t re fo rm s

As early as the 1980s, China has initiated reforms in court trials and promoted professionalism in the judicature, w ith a focus on enhancing the function of court trials, expanding the openness of trials, improving attorney defense functions, and training professional judges and procurators.

In 2004, China launched large-scale judicial reforms based on overall planning,deployment and implementation.

Through the reform process, China improved the structure of its judicial organs,division of judicial functions and system of judicial management, established a judicial system featuring clearly defined power and responsibilities, mutual collaboration and mutual restraint, and highly efficient operation,according to the white paper.

China initiated a new round of judicial reform beginning in 2008, featuring the goals of optimizing the allocation of judicial functions and power, implementing the policy of balancing leniency and severity, building up the ranks of judicial workers, and ensuring judicial funding.

The tasks of the judicial reform have been basically completed, as relevant laws have been amended and improved, the white paper said.

However, judicial reform—an important part of China’s overall political reform effort—remains a long and arduous task, the white paper says. It also urges continuous efforts to strengthen reforms w ith a goal of establishing a “just, effective and authoritative socialist judicial system with Chinese characteristics.”

FREEDOM REGAINED: Zhao Zuohai, a farmer from Henan Province who was w rong ly im p risoned for 11 years on a m urder charge, at a hostel he runs w ith his w ife, on Ap ril 20

Jiang Wei, head of an office in charge of the country’s judicial system reform, said at a press conference on October 9 that as a highly populous developing country, China still has problems in its judicial system.

Jiang adm itted that the country’s economic and social development does not match the people’s increasing expectations for social justice and its judicial system’s capability does not meet the demand for judicial service.

But the official emphasized that China’s judicial system would be based on its current reality, instead of merely a copy of other countries.

“The problems can only be solved w ith a Chinese approach and wisdom. Imitating foreign experience or foreign systems could lead to a poor outcome,” Jiang said, responding to a question about whether China’s judicial system should follow Western models.

However, he said, China is keen to learn from the experience of other countries and w ill try to incorporate judicial concepts and practices utilized elsewhere.

Righ ts p ro tec tion

In the five-chapter white paper, one third falls under a chapter entitled, “Enhancing the Protection of Human Rights.” It says that enhancing human rights protection is an important task of the judicial reform plan.

Human rights protection was included in China’s Constitution in 2004. One year ago,the death of 27-year-old Sun Zhigang rocked the country. On March 30, 2003, the aspiring fashion designer was savagely beaten to death by eight patients at a penitentiary hospital after being detained as a vagrant for not carrying an ID w ith him on his way to an Internet cafe. Since Sun worked in Guangzhou, south China’s Guangdong Province, a city more than 1,000 km from his hometown in central Hubei Province, his detention was justified by the Measures for Internment and Deportation of Urban Vagrants and Beggars, an administrative regulation promulgated by the State Council, or China’s cabinet, in 1982.

The loss of Sun’s young life drew a torrent of online sympathy and questioning over the validity of the internment regulation, as the Legislation Law stipulates that any provisions concerning deprivation of the human rights and democratic rights of citizens must be made in the form of laws by the National People’s Congress or its standing comm ittee.

Forty days after Sun’s death, the internment regulation was abolished. In M arch 2012, the phrase “respecting and protecting human rights” was w ritten into the first chapter of the revised Criminal Procedure Law asone of its basic aims and principles.

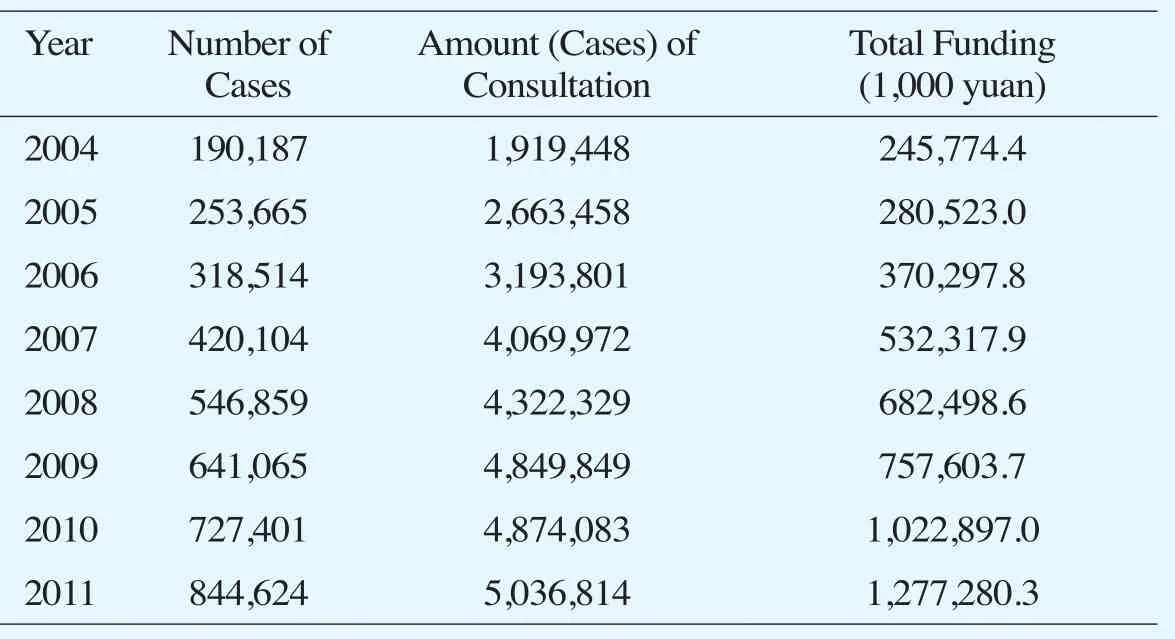

Num be r o f Lega l Assistance Cases,Consu ltation and To ta l Fund ing in Recen t Years

When the police announced the head trauma that killed 24-year-old Li Qiaom ing, who was briefly incarcerated on charges of illegal logging in Jinning County, southwest China’s Yunnan Province, was caused accidentally by inmates during a game of “hide-and-seek” in February 2009, a public uproar ensued. Li’s father, who viewed his son’s corpse, told local media that Li’s head was swollen and his body was “covered w ith purple abrasions”that were inconsistent w ith the police report.

Later investigations overseen by a commissioner from the Supreme People’s Court revealed that Li was killed by three cellmates who, after beating him, fabricated the hideand-seek story. Several police officers were also removed or punished for negligence.

The public outrage provoked by Li’s death highlighted the need to im p rove oversight of courts and prisons to prevent bullying, torture, unjustified detentions and other abuses of human rights of the accused.

To protect detainees from physical abuse, a body surface examination has been conducted on a detainee daily within seven days after he or she is sent to a house of detention. This examination system is also strictly implemented before and after a round of interrogation, as well as before and after a detainee is sent away from or back to a house of detention, according to the government white paper.

Amendment Eight to the Crim inal Law, which went into effect in May 2011,eliminates the death penalty for 13 economyrelated non-violent offenses, accounting for 19.1 percent of the total death penalty charges.

The amendment also stipulates that the death penalty shall generally not be used for people who are already 75 years old at the time of trial.

China also revised laws to provide a legal guarantee for lawyers to meet w ith suspects or defendants, access case materials and obtain evidence through investigation.

According to the white paper, from 2006 to 2011, lawyers throughout the country provided defense in 2.4 million criminal cases, up 54.16 percent over the period between 2001 and 2005.

China has gradually extended its coverage of legal assistance since 2003, and established and improved its funding guarantee system,providing free legal services for citizens w ith econom ic difficulties and parties to special cases of lawsuits, stated the white paper.

The white paper shows that the number of legal assistance cases totaled 844,624 in 2011,and more than doubled that in 2007.

The daily state payment for infringement upon a citizen’s right to freedom was increased from 17.16 yuan ($2.74) in 1995 to 162.65 yuan($26) in 2012, according to the white paper.

The State Compensation Law amended in 2010 establishes necessary offices responsible for state compensation, opens up the channels for claiming compensation, expands the compensation scope, specifies the burden of proof, adds compensation for psychological injury, increases the compensation standards, and guarantees the timely payment of compensation.

According to the white paper, attempts are made to offer inmates vocational training in order to enhance their ability to make a living after being released.

Since 2008, a total of 1.26 m illion inmates have completed literacy and other compulsory education courses while serving their sentences, and more than 5,800 people have acquired college diplomas recognized by the state, it added.