For the Love of Lamian

2011-10-14ByADAMMOORMAN

By ADAM MOORMAN

For the Love ofLamian

By ADAM MOORMAN

China is home to one of the world’s greatest culinary cultures. Diners around the globe have grown accustomed to Chinese restaurants in their cities, and to many palates kung pao chicken is as familiar as curry. However, as people living and working in China have come to learn, this huge country boasts an almost infinitely varied selection of specialities that are not known outside China.

Some of my favorite fare comes from the ranks of lesser known foods, and it can be frustrating when trying to explain to friends in the United Kingdom the kind of Chinese cuisine I enjoy. Unfortunately, no amount of description can really help them understand and appreciate foods they have never tasted,and their mental image of Chinese food remains the glistening sweet and sour pork in a silver foil tray, ordered from the local Cantonese take-away.

Probably the dish I have enjoyed most over the years in China, and one that I have never seen outside of the country, is Lanzhoulamian. They are a kind of noodle named after Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu Province in the northwest. The wordlameans to pull,which explains how the dough is transformed into long thin noodles, calledmian.

Like most things in China, these noodles have a long history. According to the commonly-accepted story, a Hui Muslim chef from Lanzhou fi rst inventedlamianin the early 1800s, during the Qing Dynasty(1644-1911). His descendants continued the tradition of making the noodles and the fame and popularity of the dish gradually grew among the local population. A Chinese friend once told me that nowadays the residents of Lanzhou eat the dish for breakfast,lunch and dinner. However exaggerated that may sound, the story does help us to understand thatlamianis important to local people in a way that goes far beyond what the English translation suggests.

The key to a good bowl oflamianis high quality, fresh, simple ingredients, and there is a memorable description to explain the appearance and contents of the meal. In Chinese, the description centers on numbers and colors:yi qing,er bai,san hong,si lü,wu huang.Yi qing—one clear—states that the soup the noodles are served in should be clear.Er bai—two white—refers to the thin white slices of radish in the soup.San hong—three red—describes the dark red chilli that provides the kick.Si lü—four green—is for the garlic bolts and coriander leaves.Wu huang— fi ve yellow—means that the noodles themselves should show the yellow of the wheat. This is all complemented by several thin slices of beef, and served piping hot.

The noodles should be made fresh and dropped straight into boiling water, and often customers can watch the whole process from their table. Many restaurants make a point of preparing the noodles in full view of the patrons, and it is really a spectacle worth seeing. The chefs fi rst knead and roll out the dough, cut off a chunk and begin to pull it into shape. With great skill they pull the dough into a long cord, then alternately stretch it and allow it to spin round itself like a telephone cord several times before deftly pulling the dough into strands of noodles that are then thrown into the pot. Customers can decide how thick they want their noodles and the chefs will prepare them to exact speci fications. I like the thick, chewy kind, whereas most Chinese diners seem to prefer the other end of the scale: hair-thinmaoxinoodles.

Althoughlamianoriginated in Lanzhou,nowadays many restaurants are actually run by Muslims from Qinghai Province, leading some Lanzhou locals to complain that their good name has been hijacked by their neighbors. If a restaurant has pictures of the Dongguan Mosque in Xining or yellowgreen meadows and snow capped mountains,the proprietors are probably Qinghai natives.Whichever province they are from, the men in the restaurants usually sport white skullcaps and the women wear headscarves that cover their hair and necks. In keeping with Islamic traditions, many places don’t serve alcohol and also ask that customers to leave their bottles at the door, so it is important to respect the rules of the house in these restaurants.

The simplicity of the noodles reflects their place of origin. Lanzhoulamianwas created in the harsh, arid conditions of the northwest, and every bowl has a filling,hearty feel that is lacking in some Chinese dishes. As the winter begins to creep closer day by day, enjoying a steaming bowl oflamianis a great way to get the energy and warmth needed to brave the bitter Northern Chinese winter. When you next sit down to eat a bowl, chopsticks in hand, remember as you enjoy your fi rst mouthful with a loud slurp, that millions of others are happily slurping with you.

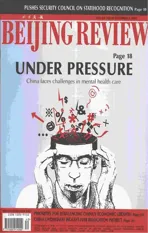

AS THIN AS HAIR: A chef is pulling the dough into long thin noodles at a gourmet festival in Gansu Province, home of lamian

EXPATS, WE NEED YOUR STORIES!

If you’re an expat living in China and have a story or opinion about any aspect of life here, we are interested to hear it. We pay for published stories.Submissions may be edited.E-mail us at contact@bjreview.com.cn Please provide your name and address along with your stories.

The author is an American living in Xi'an