A Plague of Bailouts

2011-10-14ByLOHSUHSING

By LOH SU HSING

A Plague of Bailouts

By LOH SU HSING

The EU starts to worry about a possible domino effect from bailouts dragging down the entire euro zone

While there has long been anticipation of Portugal’s need for an economic bailout, the country’s formal request on April 6 still dealt a sobering blow to the current crisis in the EU.Portuguese banks are already heavily reliant on assistance from the European Central Bank (ECB). But as the markets demand ever higher returns on new government debt instruments, and with the government’s recent resignation fueling market fears, Portugal had little recourse but to follow in the steps of Greece and Ireland and turn to an EU bailout.

Since the start of the financial crisis,Europe has been plagued by overwhelming problems of huge budget de fi cits, low growth and savage cuts on spending. This has undoubtedly been the most severe test the euro zone has confronted since its inception. With the volatility the euro has experienced over the past year, and no clearly mapped solution to the crisis, the looming question remains:What does the future hold for the decade-old European currency project?

The EU has been scrambling to find solutions to contain the ripple effects of the current sovereign debt crisis. At a summit in Brussels in March this year, EU leaders underwent discussions to adopt a comprehensive strategy for stabilizing the euro zone,and an agreement was reached to extend the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF) to 500 billion euros ($722 billion)—effective lending capacity of 440 billion euros ($636 billion)—with triple-A status and establish a permanent European Stability Mechanism by 2013. Signi fi cantly, as a clear indication of fears Greece might default, interest rates on loans Greece has taken out were reduced by 1 percentage point.

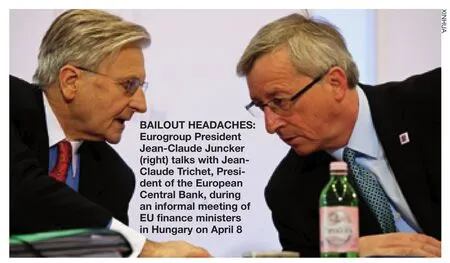

When EU finance ministers met in Hungary this month, Portugal was clearly top of the agenda. Despite these measures,overall sentiment about the crisis remains negative for a number of reasons.

First, there appears to be no end to the crisis in sight. The bailout of Greece was intended to prevent contagion and a systemic crisis. But in November last year, Ireland went under swiftly but was subsequent bailed out to salvage its situation. Yet, now Portugal is in need of aid. The domino effect of the crisis has stretched the limits of the amount of debt eurozone member countries are willing to shoulder.

With countries like Finland and Germany facing upcoming elections, their leaders are not in the best of positions to convince their populations to continue bailing out fellow EU members. EU leaders have to tread a delicate balance between pandering to domestic demands and adopting a longterm view by taking measures that would bene fi t the euro zone in the long haul.

More importantly, the bailouts have only offered short-term relief to markets, by providing liquidity and staving off insolvency. There remains the possibility countries like Greece might default on their debt, setting off a secondwave of crisis. The only feasible long-term solution to the crisis is economic growth to enable the indebted countries to pay off their mounting debt. Just as an upward economic spiral sets in motion a positive cycle, the EU is now confronted with a negative downward spiral,as the loans lock bailout recipient countries into austerity measures for years, and paying off this debt adversely impacts the very growth needed to pay off the debt.

The bailout of Portugal is relatively light,estimated at 80 billion euros ($116 billion),compared to 85 billion euros ($123 billion)for Ireland and 110 billion euros ($159 billion) for Greece. But there is still the lingering worry Spain might be next. Spain has an unemployment rate of more than 20 percent, the highest in the EU, and is struggling to deal with a banking crisis and the collapse of its property bubble.

Spain also has an economy that is far larger—Greece, Ireland and Portugal each account for approximately 2 percent of the eurozone economy, while Spain makes up about 10 percent. A bailout of Spain would likely stretch the EFSF considerably. In addition, Spain is one of the major contributors to the EFSF (Germany contributes 27 percent, France 20 percent, Italy 18 percent and Spain 12 percent) and its bailout would exacerbate the problem of fewer and fewer countries footing a bailout bill that keeps growing. There is also fear that further bailouts might encourage economic laxity in pro fl igate governments.

Second, it has proven dif fi cult to formulate policies and actions widely beneficial across the euro zone and able to address the problems of member countries on different speeds of recovery. For instance, the ECB raised its interest rates on April 7 for the first time since July 2008 due to prolonged concerns about inflation. While this is no doubt favorable for stronger economies like Germany, it is apparent countries like Greece, Ireland and Portugal that are struggling with deficit and debt crises would be negatively affected.

The EU debt crisis has undermined confidence in the EU mechanism,and has far-reaching consequences extending beyond the economic sphere

Even among the countries receiving bailouts, the causal factors for their economic woes vary and require different solutions.Greece ran large structural deficits and engaged in misreporting of economic data to stay within euro-zone requirements, eventually crumbling under overwhelming debt.Ireland lapsed into dire straits when it had to bail out its over-leveraged banking sector,which was hit by the collapse of the real estate market in the wake of the fi nancial crisis.Portugal has long been lingering in economic doldrums due to general lack of competitiveness and governmental irresponsibility.

Third, the EU debt crisis has undermined con fi dence in the EU mechanism, and has farreaching consequences extending beyond the economic sphere. The disproportionate burden shouldered by member states due to the imprudence of other member states casts doubts on whether further integration in other domains is indeed bene fi cial and desirable. The debt crisis has underscored fact that the euro zone as a whole has been forced to assume responsibility for the failings of individual member states that have not demonstrated their resolve to put their internal politics in order.

Due to the strength of opposition parties,Portugal’s parliament resolutely rejected the austerity program the European Commission and the ECB endorsed. Despite having benefited greatly from EU membership, Ireland initially voted against the Lisbon Treaty, an amended version of an aborted EU Constitution,and yet now is relying on an EU bailout. Ireland has also refused to increase its corporate tax rate, against the recommendations of the EU.

There is also skepticism among EU member states on the interpretation of the Lisbon Treaty, as the EU bailout of Greece and Ireland was justi fi ed using Article 122 of the treaty governing the European Monetary Union which states if a member state is “in difficulties or is seriously threatened with severe dif fi culties caused by natural disasters or exceptional occurrences beyond its control,” the EU may grant fi nancial assistance to the member state concerned. There has been much controversy over whether fiscal irresponsibility counts as “exceptional occurrences beyond its control.”

Despite these concerns, there remains hope the EU might emerge battered but intact from the crisis. The sovereign debt crisis has showcased France and Germany’s commitment and resolve to safeguard the euro. The lending capacity of the EFSF is enough to fund a Portuguese bailout, and it is part of a buffer also including funds from the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund. Even in the event of another major bailout or new demands from current recipients, it is likely the EFSF will be able to cover them, though not without signi fi cant strain and unpopularity.

The European Commission has indicated the Portuguese aid request will be dealt with “in the swiftest possible manner,” and unlike the bailouts of Greece and Ireland, there has been no new wave of panic, as markets had been primed for a Portuguese bailout and were already behaving in anticipation of it. EU leaders have started to address worries about the euro zone’s fi scal soundness, and market distrust of debt, and appear to be moving closer to trying to find a eurozone-wide solution, rather than merely fi re fi ghting and passively bailing member states one after another.

The very origin of the EU was built on a foundation of overcoming crises. It has time and again proven its mettle at overcoming the odds. Should the EU tide over this crisis and use it as an opportunity to address structural gaps in the euro zone, adopt necessary fi nancial reforms, and undertake greater political coordination and institutionalization,it will gain greater credibility in the process,or at least not negate the laudable progress it has made in the past fi ve decades.

(Viewpoints in this article do not necessarily represent those ofBeijing Review)

The author is an associate fellow with Chatham House, London