澳大利亚被称颂的建筑:国家建筑奖计划及其对设计文化的影响

2010-07-30亚历克赞内斯许亦农

亚历克·赞内斯 许亦农

澳大利亚建筑师协会建筑奖计划

澳大利亚皇家建筑师协会[1](RAIA),现改名为澳大利亚建筑师协会,是代表这个国家建筑行业的最高职业机构。RAIA的使命是“推进会员利益、职业水准和当代建筑实践;扩展并倡导建筑师和建筑对我们社会、经济和文化可持续生长的价值。”[2]

自1981年起,RAIA每年举办一次全国建筑评奖活动;其透明的同行评议挑选机制经历年发展不断改进[3]。建筑评奖计划以严格、公正的评审过程著称,并允许落选者在之后若干年中随时再次参选,以削减任何年度评委会决定中潜在的同行评议的偏见。有资格参加评选的是那些既在澳大利亚注册又是RAIA成员的建筑师的作品;总体来讲,因表彰澳大利亚注册的、RAIA成员的建筑师在澳洲和国际上所创造的最高标准的建筑成就,这个评奖计划得到普遍认可。

RAIA评奖体系包含一个限定条件,即并非所有最高标准的建筑成就都得到表彰,因为并非每个在澳大利亚建成的重要建筑都有资格参选。一些在澳大利亚建造的杰出作品不是由RAIA成员设计的。但更引人注目的是,一些建筑行业人士指征评委会所作的某些有争议、偏见并因此令人失望的评定。既然评委会成员每年更换,那么,随后的评定有时会推翻之前评委会的评定,从而证实了允许重新入选能够在某种程度上减少偏见性的作用。

评奖计划将地方奖项(即州、地级奖项)与国家级评选过程结合起来。由地方独立评委会选出的地方获奖建筑自动取得参加国家级评选的资格。国家级建筑奖代表着从澳大利亚各地评选出的“精而又精”的建筑成果,也包括一个专为国际业务而设的特殊奖项。[4]

RAIA建筑评奖计划的宗旨与给予RAIA成员的、诸如授予荣誉和奖励等其他形式的表彰没有差别。对评奖计划的宗旨的诠释使我们注意到下面两段至关重要的声明:

(ii)发展公众对建筑的重要性和设计价值的深刻意识和理解,并且

(iii)鼓励建筑师为建筑的卓越品质而努力,以促进建筑学的发展与进步。[5]

这些宗旨的构架总体来说暗示着建筑设计中的卓越成就与社会改良的联系。那些要求评委会考虑的具体评审标准里包括了对公共利益更加详细的内容的评价。

评价参选作品的评审标准是由2005、2006两年对评奖方针的重新审定发展而来;很简短,所以在这里全部列出来[6]。第1、2、3、7和8条标准尤其为评委会评价对影响公共福利的建筑成就提供了更明确的指导。

1. 概念框架:设计项目的基本原则、价值、核心概念以及哲学思想。

2. 公众和文化利益:设计项目提供的公共便利设施和为公共领域做出的概念性贡献。

3. 建筑形式与环境的关系:与新旧状况发生密切关系的设计概念。

4. 功能编排问题的解决:根据设计任务书而评价的功能方面的表现。

5. 相关学科的综合协调:工程技术人员、景观建筑师、艺术家以及其他专业人员对项目成果的贡献。

6. 造价与价值的关系:与资金问题相关的各项决定的有效性。

7. 可持续性:由设计带来的环境方面的益处。

8. 对业主和使用者需求所做出的反应:从任务书解读出来的额外的、服务于业主或使用者以及社区的益处。

这些评审标准表明了评委会需要考虑的各种问题之间的平衡。总之,一项建筑作品是否足以获得国家建筑奖,必须取决于是否满足这样的标准:(1)通过清晰表达建筑概念而对任务书做出反应;(2)其结果在某种程度上具有公共福利的意义。

获奖名单公布时吸引了国家和地方媒体关注。对年度评奖结果的关注具有广泛的基础,并受到报刊杂志和电视等媒体的广泛报道。[7]这表明,由建筑行业评定的全国最高建筑成就,使评奖计划受到很多澳大利亚人的关注。那些涉及公共利益问题的评审标准把媒体的焦点集中到对社区的意义问题上。尤其重要的是,评奖计划通过严格、独立、诚信的评选过程而获得的声誉,确定了RAIA获奖建筑在社会上的认可和影响。建筑行业对澳大利亚社会来说很重要,而每年对获奖建筑的表彰和公开讨论,可以认为是RAIA为这种认知做出的贡献。

2007年-2009年RAIA公共建筑和商业建筑奖项中重要的获奖作品

RAIA泽尔曼·考恩爵士奖[8]被认为是享有最高声誉的澳大利亚公共建筑的奖项,通常被称作RAIA奖项中的“名人”奖。与其相当的“名人”奖是RAIA哈里·赛德勒商业建筑奖[9]。尽管评委会在任何奖项中可以发奖的数量理论上不限,但每一奖项中的名人奖每年只能颁发一次。[10]典型的情况是每年在每个奖项中都有一定数量的获奖作品。

下面几个例子是从2007—2009年度公共和商业两个建筑奖项的获奖作品中挑选出来的[11],目的在于探讨这些建筑对澳大利亚设计文化的影响。

1 昆士兰州立图书馆外景/State Library of Queensland, exterior view

2 昆士兰州立图书馆内景/State Library of Queensland, interior view

3 现代艺术展览馆(GoMA)外景/Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA),exterior view

4 现代艺术展览馆(GoMA)内景/Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA),interior view(1-4 摄影/Photo: John Gollings)

昆士兰州立图书馆,布里斯班,昆士兰

2007年,RAIA泽尔曼·考恩爵士国家级公共建筑奖由多诺文/希尔建筑师事务所(佩德尔/索普建筑师事务所联合)设计的昆士兰州立图书馆获得。任务书提出的一个重要目标是加强社会人口使用图书馆的范围和程度,以发展社区中公共建筑的文化价值。

建筑师对此做出的响应是创造发人深省、引人入胜而又充满自信的建筑。戏剧性的外部形式和色彩的运用支配着主要入口和其河滨景象,并因与常规而拘谨的典型公共图书馆建筑截然相反而令人难忘。

对多诺文/希尔来说,室内空间可比作一座“微型城市”的建造,诸多道路引向各个不同的特殊功能区域;这些区域由外部景致强调出来,并且由不同空间和材料体验组成的矩阵进行布局安排,而令使用者得到最大限度的享受。

这座图书馆没有借助建筑强调图书馆的权威和其在社会中的教育角色。相反,它传达的是这样一种精神:即开放型的探索、灵活的学习途径,以及运用当代技术和学习方法而获取信息的社会枢纽。

评委会赞辞提到了这一建筑作品“追求并激发与公众互动的远大志向”[12]。这一志向与在整个澳大利亚的加强公众对政府图书馆设施的意识和使用这一基本目标相吻合。从这个意义上来说,多诺文/希尔探求了大型公共图书馆建筑的一个新的设计范例,借以扩展图书馆在社会上的作用。

现代艺术展览馆,布里斯班,昆士兰

毗邻昆士兰州立图书馆的是由Architectus公司设计新建的现代艺术展览馆,与前者在同一年获奖。这两栋建筑与包括由罗宾·吉布森及合伙人于1982年设计的昆士兰艺术展览馆等其他杰出建筑构成了昆士兰文化街区的一部分。

现代艺术展览馆的外形以一个巨大坚实的出挑屋顶结构为主导,如此设计可以荫蔽建筑外墙,减少其热负荷。对屋顶形式所做的细部处理使出挑更加戏剧化,强调轻盈之感;其设计或许受到当地建筑文化的启发,也或许由考虑昆士兰气候条件派生出来。

参观者适宜的艺术体验和公共交通流线的清晰表达,对这二者的关注决定了设计的组织原则。一系列相互连接并强调利用自然光和虚体的展厅空间,明确勾勒出其空间体验和室内特色。

现代艺术展览馆为文化街区做出的另一贡献,是使人们可以从3个截然不同的公共开敞空间进入展览馆。建筑意向是以一个亭子的形式,融入并支持临近的公共开敞空间,以强化其作为城市公共便利设施的价值。[13]

政府在重大文化设施上的建筑投资一直是澳大利亚文化和经济发展的一个基本因素。不过,政府在扮演授权代理角色时,有时会出现一些严重问题,致使在建造过程中威胁到建筑品质。在建造过程中维护设计完整性的问题上,RAIA积极支持了负责现代艺术展览馆和州立图书馆的那些建筑师。[14]

布里斯班文法中学彻乐尔·赫斯特创造性学习中心,布里斯班,昆士兰

2008年,布里斯班和昆士兰的建筑师又一次夺得了令人垂涎的泽尔曼·考恩爵士奖,这次获奖的是一家名为“m3建筑”的事务所。获奖建筑是由布里斯班文法中学—— 一所私立女子中学委托的一处新的学习中心。

这是一座“创造性艺术”建筑,任务书要求在一栋建筑中为艺术、音乐、戏剧和技术活动提供设施。学校希望得到一种鼓励使用者自主的教育体验的物质环境,建筑设计也就从这个要求衍生出来。其结果是建筑空间围绕两个特色鲜明的主要部分组织起来,分别为学生有计划编排的和随机的两种学习体验提供便利。有计划学习的空间共6层,容纳正式教学和学习所需的各项设施,如教室和为特殊目的设计的厨房、学校商店,以及艺术、音乐和戏剧空间。紧靠其旁是竖向贯通的随机学习空间,由一大型伸展屋顶覆盖,以避风雨。由此产生的非正规空间有助于一种新的社会环境,促进随机、合作式学习方法和独立思考过程,而这正是这所学校教育哲学要求的创造性实践的一项基本原则。

结果是近一半的建筑体量全部服务于一种新型社会学习经历和环境。多层、随意设置的开敞室内空间,除了为其侧面围合起来的各个主要功能空间提供交通便利之外,没有特定的功能安排,这一建筑因此令人难忘。

布里斯班文法中学的创造性艺术教学和学习的目标,为一种新型建筑空间提供了启示。业主的任务书大胆地利用建筑为创新教育实践服务。大面积室内开敞空间是学校教学法不可或缺的一部分——为学生之间通过群体交往而得到非正式教学和学习体验提供空间。

建筑师同时还发展了其他一些反映地段条件的独特而赋于表达的要素。比如,校园与新建筑的主要连接就是直接通过这个新的随机室内开敞空间达到的。混凝土结构连续多变的几何形式为建筑带来生机勃勃的性格,使校园主要交通轴线的体验戏剧化。在对面,这座建筑成为沿着主路和运动场地看过来的视线终点,表现为一道有视觉特性的幕墙,创造出一种视觉上似是而非的效果,成为另一种向公众展现学校充满活力的表达因素。

从环境管理角度讲,这座建筑将场地上的灰水(即厨房、沐浴和清洗等用水——译者注)回收利用、相关的节省能源、最大限度地减少废物等一系列技术结合起来。

评委会赞辞称之为 “具有率直的细部处理,深思熟虑而坚实的”建筑。“它不传达任何毫无意义的信息——当考虑年轻女性的教育时,悉心思忖这项大胆而目标明确的建筑作品实在令人振奋。”[15]

建筑能给实现教育目标带来价值,这个项目的获奖使人们能更广泛地理解这一点。其创新在于通过抓住学生社会方面的经历而强化随机学习机会的一种新型空间,而这或许可以运用到澳大利亚其他中学的建筑设计上。如果把这个理念同政府要求澳大利亚中学设施必须具有的教育空间各项标准结合起来,将使这一教育和建筑理念被更广泛地接受。

奈杰尔·派克学习和领导中心,墨尔本文法中学,墨尔本,维多利亚

在同一年,另一所私立中学建筑,即约翰·沃德尔建筑师事务所设计的墨尔本文法中学的奈杰尔·派克学习和领导中心,也获了奖。

这座建筑尤其强化了公共区域,不论是从旁边繁忙的街道上,还是在公众可以进入的、联系校园其他建筑的娱乐空间里,都可以体验到。利用独特的玻璃和砖墙细部处理,其形态看上去好像在不断演化,引发人们对建筑的关心与乐趣。

内部各种设施安排的随意性促进了学生非正式的学习和交往方式。其装修与布置丰富而大方,自然光的大量运用强化了建筑空间质量。建筑内部和外部设计为学校提供了引人入胜的学习环境——有助于提高学生和教职员工学习和工作的质量,这一点从对建筑师成就的热情评价中得到证实。

气候控制是设计的一个重要考虑因素,太阳能的获取程度高得异乎寻常,从而弥补了严冬季节的热量损失。利用漫长的暑假期间进入建筑的学生数量减少的机会,又对夏天的热量进行了一定控制。

巧妙地处理建筑各方面物质性特点,以便通过赋于想象力的空间、光线和造型来强化教学和学习体验,这些都没有出现在政府的中学建筑设计指导方针里。这些设计指导方针也不强调非正式和计划式学习空间的结合。因此,在澳大利亚,由政府委托设计的标准中学建筑的物质环境,还没有普遍采纳奈杰尔·派克学习和领导中心的这种空间或建筑上对这种需求的反响。

国家肖像展览馆,堪培拉,澳大利亚首都直辖区

2009年,泽尔曼·考恩爵士奖授予总部设立在悉尼的约翰逊/皮尔顿/沃克尔建筑事务所设计的国家肖像展览馆。

5 彻乐尔·赫斯特创造性学习中心内景,非正式教学空间/The Cherrell Hirst Creative Learning Centre, interior view, informal learning space

6 彻乐尔·赫斯特创造性学习中心外景/The Cherrell Hirst Creative Learning Centre, exterior view(5.6摄影/Photo: Jon Linkins)

7 奈杰尔·派克学习和领导中心外景/Nigel Peck Centre for Learning and Leadership, exterior view(摄影/Photo: Trevor Mein)

8 奈杰尔·派克学习和领导中心剖面/Nigel Peck Centre for Learning and Leadership, section(John Wardle Architects)

肖像展览馆坐落在堪培拉的议会三角区内,毗邻是规模庞大、多次获奖的建筑作品,即爱德华兹/马迪干/托尔兹罗和布里格斯事务所设计的国家美术馆(1982)和澳大利亚高等法院(1980)。与邻近建筑相比,国家肖像展览馆形象低矮,强调的是其景观环境和由内向外的视野。建筑的横向造型由入口处一个戏剧性出挑结构强调出来,从而与临近的爱德华兹/马迪干/托尔兹罗和布里格斯的那两座庞大得多的建筑在规模和竖向特征上形成强烈对比。

精心的室内设计建立起一系列尺度亲切的相互咬合空间,很适合观赏肖像艺术。室内性格的形成则直接来自于建筑的材料和结构,并通过自然光在每个展厅中的散射而得以加强,从而将人工照明减少到最小限度。参观者被引导穿过一系列由自然光和结构限定的线性展厅。建筑师还指出,他们从数学的黄金分割或菲波纳契数列派生出对人脸比例的理解,借以发展这里运用的空间概念。室内建筑有一种镇定宁静的效果,放慢了参观的速度,以适合对肖像的凝视和思考。

对建筑中安置艺术品的关注,对观赏冥思艺术的人为体验的考虑,为这种类型的建筑提供了别具一格的设计焦点。评委会的赞辞征引了路易·康的金贝尔美术馆(1972)的先例,作为诠释这一建筑概念的指南。[16]这与近来的一种趋势形成对照,那就是将弗兰克·劳埃德·赖特初始的古根海姆博物馆——采用一个戏剧性的中央空间和周边展览区域以组织空间体验——作为建筑典型。

评委会同时还就资金问题对政府提出了批评——考虑到藏品的重要性和名气,政府没有为这个项目投入足够资金,以致设计无法提供与其规模相应的设施。政府对文化类建筑支持的匮乏问题其实早在2007年文化项目的评奖中就已被提出。

万圣中学,悉尼,新南威尔士

与国家肖像展览馆同年获奖的是与澳大利亚的希腊东正教会相关的一所小学,经私人委托由悉尼的坎达勒帕斯联合事务所设计。

与2008年获奖的两所学校不同,这件作品明显是在更低的预算限制下构思的。尽管如此,这是一个具有非凡表现力、引人入胜的建筑作品,强化了相对常规的教学空间体验,从而充实了学生和教职人员的学校生活。

该设计把普通教室分布在4层建筑中,由连续的通道次第连结起来,从通道可以获得外面学校操场和街对面校园其他部分的各种景致。对砖石材料和空隙填充因素的娴熟应用,不仅给这一设计手法带来直接而积极的影响,而且漫步其中时,会感到不断暗示着的简单排列的空间中嬉戏尝试的一面。

评委会的赞辞[17]又一次间接提到这件作品在指导政府投资的学校建筑改进方面的价值。这一建议是有针对性的:最近完成的一些政府学校建设项目仅仅依赖于标准模式的平面布局和三维空间组织,没能达到建筑设计起码的标准,对场地特殊性也缺乏考虑。

尤丽卡大厦,墨尔本,维多利亚

由凡德/卡匝里蒂斯建筑师事务所设计的尤丽卡大厦,是2007年RAIA哈里·赛德勒商业建筑国家大奖的得主。这栋建筑在其开发出来的80多层空间中综合容纳了一系列用途——公寓、旅游设施、多功能空间、旅馆和展示空间。这种复杂的功能范围反映出澳大利亚近来发展的一种城市建筑类型,通常被称为“混合用途”开发设计。除了一些包括哈里·赛德勒联合事务所的设计在内的重要案例之外,从历史上讲,澳大利亚高层设计提供了基本适宜的常规建筑,但在文化层面上几乎没有鼓励大众和包括建筑历史学家在内的建筑行业对它们的关注。

尤丽卡大厦则是赢得大众想象力的高层建筑中的一个典范,现在也成为墨尔本城市的重要标志之一。戏剧化的形态和修长的比例,从南面或北面看尤其如此,尤丽卡大厦的设计为城市性格做出了积极的贡献。色彩和玻璃的运用明确了其外部性格,而在白天也起到了独特的反射效果。

澳大利亚城市一般来说都是低密度的,高层居住建筑不是人们向往的开发类型,所以通常不被接受。尤丽卡大厦却在建成后马上被认为是墨尔本市中心的重要建筑,并且为公众更广泛地接受这种形式的住房开发做出了贡献。作为更高密度居住建筑类型之例的尤丽卡大厦,对它的接受非常重要,原因包括通过建筑而降低国家碳排放的需要。

水滨广场,布里斯班,昆士兰

与尤丽卡大厦同年获得相同奖项的哈里·赛德勒联合事务所设计的水滨广场,是“综合用途”高层建筑类型的另一个范例;在这里,下面是停车场,其上为写字楼,顶部用作公寓。地面层构想为步行环境的延伸,从而将这层建筑面积减小到最低限度;同时把商业和居住入口分开。

与尤丽卡大厦不同,水滨广场中每一项功能都可以在建筑外部处理上辨别出来。砖石材料的形式和外窗组合的变化反映出每一种使用功能,从而获得了错综复杂的建筑处理效果,远近皆可轻易识别。这就确保了这座建筑成为城市天际线中的一个地标。

水滨广场是这位建筑师创作的顶峰,给业已丰富的高层建筑遗产增添了光辉,也是具有创造力的砖石建筑形式的一套新的处理手法。水滨广场反映了澳大利亚以混凝土为主要材料的高层建筑设计的不断发展。

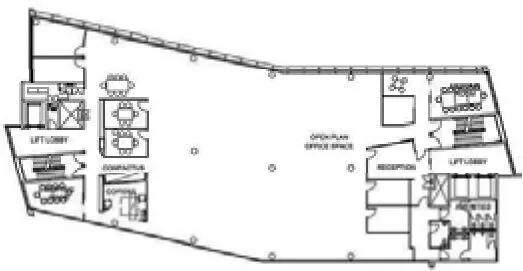

休姆市政厅办公楼,休姆,维多利亚

澳大利亚各个郊区中心很少展示当代商业建筑的佳作。但是,2008年的哈里·赛德勒奖却落到建筑师里昂斯的手中,作品是休姆市政厅办公楼[18]——坐落在一处购物中心停车场旁边、距高速公路和火车站不远的一座6层建筑。

在形式、色彩和积极的地面使用等方面,此建筑设计刻意的大胆之举丰富了相对平淡的城市环境。办公人员和来访者可以直接意识到建筑带来的积极而实在的价值,以及市镇中心经过改善的公共领域。内部空间根据有雕塑感的外形而规划设计,从而获得了令人难忘的交通流线,创造了愉悦的工作环境。这座建筑同时结合了先进的节能设计和技术,以响应业主致力于获得更大程度上可持续的城市环境。

休姆市政委员会旨在借助建筑来展示在地方政府资金拮据的典型状况下,他们对商业发展的一种不断进取的态度。建筑能够通过创造更多可持续性的、具有文化价值的地区中心而有效地改进城市环境,其市政办公楼就是这样一个典范。这个项目向人们表明了由政府研发并实施的周全、具体的项目设计任务书所反映出来的领导能力和作用。

摩纳哥领事馆,墨尔本,维多利亚

与休姆市政厅办公楼同年获奖的还有墨尔本城市小巷中一块小地段上的建筑,即由麦克布赖德/查尔斯/瑞安建筑事务所设计的一栋为业主特别设计建造的办公用房。内部和外部均构思为一篇折叠、复杂几何体中的视觉小散文,给使用者和它所处的小巷中行人的体验带来活力。

视觉上暗指领事功能的双关语丰富了对建筑的解读,包括一个仅能容纳一人的高点出挑阳台,暗示着向小巷里人们演讲的那令人尊敬的场所;也包括底层一块极小的草地,或许象征摩纳哥公国。这栋建筑的其他方面则直截了当,一个不大的核心部分将室内空间增至最大限度。这栋建筑最后一个贡献是通过对形式和材料精确的运用,使人们体验到特殊的视觉趣味,进而丰富了此处的公共区域。

新阿克顿东楼,堪培拉,澳大利亚首都直辖区

2008年另一项商业奖,授予凡德/卡匝里蒂斯建筑师事务所设计的新阿克顿东楼,一个由零售空间、办公区域和公寓组成的8层混合用途开发项目。

9 国家肖像展览馆外景/National Portrait Gallery, exterior view

10 国家肖像展览馆内景/National Portrait Gallery, interior view

11 万圣中学外景/All Saints Primary School, exterior view(9-11摄影/Photo: Brett Boardman)

12 万圣中学剖面/All Saints Primary School, section(Candalepas Associates)

地面层步行者的体验来自于历史建筑肌理与围绕着庭院和宽阔交通路径而设计的新元素之间周密的整合关系。特别委托设计并与建筑结合在一起的当代艺术作品给来访和居住者的体验带来积极的影响。这些艺术作品丰富了那些本来深藏内部的、把各个主要入口门厅与零售活动连接起来的交通路径空间。建筑形态在一定程度上是从多变的内部使用和包括上层公寓的景观利用等地段的具体特点演化而来。

堪培拉大量的景观处理常常缺乏构思,其邻近建筑一般都从公共界面退后,因此,街道空间得不到整合;那么,在这样一座城市里,新阿克顿东楼给人以全新的体验。这栋建筑因而增强了公共空间的都市性格,也为堪培拉未来城市商业建筑树立了一个典范。

常青藤夜总会,悉尼,新南威尔士

2009年,常青藤夜总会获得了哈里·赛德勒奖;设计者是伍兹/巴高特建筑师事务所,合作者包括麦利瓦尔集团公司和海克尔/费兰/古瑟力室内设计事务所。评委会的赞辞称这一开发项目为“既有罗马浴室,又有豪华餐厅,还有幽雅得体的聚集场所。”[19]

常青藤夜总会是悉尼的娱乐、招待和某种意义上的幻想性质的建筑最充实的范例,是一处主要为年轻人消费的聚集场所,里面设有餐厅、舞厅、屋顶游泳池和散置的小型娱乐空间,以吸引各种年龄的顾客。

在澳大利亚,这种建筑类型设计的标准一般不高,通常依赖于简单的围合形式为装饰起来的室内各项功能提供空间。这类建筑的例子包括许多体育俱乐部、结婚和其他形式的娱乐场地或赌博场所。常青藤夜总会打破了这种单调设计方法,在过去被人冷落的后街小巷空间中创造各种新的使用内容,用建筑彻底改进公共领域。在作为悉尼历史性最强的街道之一的乔治大街上,这一建筑表达反映出这个项目计划的乐观意向。

这种建筑类型获取国家级建筑奖极为少见。这或许反映出一个事实,即如此规模的娱乐场所承担着实实在在的城市设计、建筑设计和室内设计的责任,在澳大利亚的确前所未有。

建筑奖对澳大利亚设计文化的影响

获奖建筑不仅在全国广为宣传,从而引发大范围的公开讨论,而且影响到每一作品使用者和参观者的日常生活,这是因为每个奖项被评价和传达出的意义都在于其文化价值。这种公开化的状况既促进了获奖建筑师的设计生涯,也强化了他们的影响。珍视建筑文化价值是建筑师共同的抱负,对这一价值的认可既然得到公众的理解,那么,总体上讲,整个建筑职业也就从这一过程中受益。

如前所述,RAIA的使命是“推进会员的利益、职业水准和当下的建筑实践;扩展并倡导建筑师与建筑学对于我们的社会、经济和文化可持续生长的价值。”评奖计划清楚地与这些目标保持一致,坚持诚信的评审标准和透明的挑选过程,并确保大部分评委会成员来自做实际工作的建筑师。

在上面列举的实例中可以看到,最近获奖的中学建筑项目都是由私营企业资助的,尽管这个建筑类型的多数建设都是通过政府投资和管理过程实现的。3年多来,评奖计划中没有任何一项政府拨款兴建的学校建筑,这一事实表明在公立和私立学校建设的不同范围内,建筑标准已分道扬镳了。

国家和州级政府的作用也体现在授予主要文化基础设施的奖项中,特别是在伴随奖项而来的建筑行业对事实陈述之中——获取和实施的方法都需要改革,以便更加合理地反映这个建筑类型的设计和建造工作的复杂性。在地方政府的层面上,地方商业建筑的获奖鼓励了对结合城市改善和先进环境设计的建筑卓越品质的支持。

对地方性的关切在一些获奖作品之中很明显。这些作品突出显示了具体建筑业务的不同状况、地段特殊性的设计问题,以及影响地方建筑师设计着重点的文化环境。布里斯班的现代艺术展览馆和墨尔本的摩纳哥领事馆就是这种建筑的实例,其成就和特点在某种程度上来自于常常在具有感召力的建筑名流指导下的地方学术机构的文化影响。

RAIA评奖计划积极为澳大利亚建筑发展做出贡献。评奖计划在建筑行业里的参与指数很高,并且激发了公众相当大的兴趣。获奖作品在地方社区中受到尊重,而这又会影响那些在管理维系建筑环境上起主要作用的未来几代业主和政策制定者。□(本文图片来自:澳大利亚建筑师协会建筑奖)

The RAIA architecture awards program

The Royal Australian Institute of Architects[1](RAIA), now renamed as the Australian Institute of Architects, is the peak professional body representing the profession of architecture in this country. The mission of the RAIA is to: “advance the interests of members, their professional standards and contemporary practice; and to expand and advocate the values of architects and architecture to the sustainable growth of our community, economy and culture.”[2]

The RAIA has conducted an annual national architecture awards program since 1981 using a transparent peer review selection mechanism progressively developed over the many years of operation.[3]The architectural awards program has a solid reputation for rigorous and fair assessment processes, with opportunity for re-entry in successive years to ameliorate potential peer review bias in the jury decisions of any year. Overall, the awards program is commonly acknowledged for recognizing architecture of the highest standard, produced in Australia and internationally, by Australian registered architects who are also members of the RAIA.

Embodied in the RAIA awards system is the qualification that not all architectural works of the highest standard receive recognition, as not every work of architectural significance produced in Australia is eligible for submission. There is excellent work built in Australia by architects who are not members of the RAIA. But more notable is testimony to controversy,bias and consequent disappointment over some jury decisions from members of the architecture profession.As jury membership changes every year, subsequent decisions sometimes reverse previous jury assessments confirming the value of permitting re-entry to ameliorate, to some extent, the effects of bias.

The award program integrates regional awards (i.e.awards at State and Territory level) into the national selection process. Awarded regional architecture as selected by independent regional juries becomes, in effect, eligible for national recognition. A national award represents the‘best of the best’selected from every region in Australia and includes a special category for international practice.[4]

The aims of the RAIA award program are not distinguishable from other forms of RAIA member recognition such as bestowed honours and prizes.Interpreting the aims of the award program brings to focus two most relevant statements quoted as follows:

(ii) develop high public awareness and understanding of the importance of architecture and the value of design, and

(iii) encourage architects to strive for excellence in architecture and thereby promote the advancement of architecture.[5]

These aims are framed in general terms implying links between excellence in architecture and the betterment, of society. Within the detailed evaluation criteria for awards that juries are required to consider is assessment that includes more specific outcomes that serve the public interest.

The evaluation criteria for judging entries developed as a result of the 2005/6 awards policy review are brief and thus are noted here in full.[6]Criteria 1, 2, 3, 7 and 8 in particular give more explicit direction to guide the jury towards evaluating outcomes that include impacts of public benefit.

1. Conceptual Framework: Underlying principles,values, core ideas and philosophy of the project.

2. Public and Cultural Benefits: The amenity of the project and its conceptual contribution to the public domain.

3. Relationship of Built Form to Context: Concepts engaged with new and pre-existing conditions.

4. Program Resolution: Functional performance assessed against the brief.

13 尤丽卡大厦外景/Eureka Tower, exterior view

14 尤丽卡大厦鸟瞰/Eureka Tower, aerial view(13.14摄影/Photo: John Gollings)

15 水滨广场主入口/Riparian Plaza, main entrance(摄影/Photo: Eric Sierins)

16 水滨广场3D模型/Riparian Plaza, 3D model(Harry Seidler & Associates)

5. Integration of Allied Disciplines: Contribution of others, including engineers, landscape architects,artists and other specialists to the project outcome.

6. Cost/Value Outcome: The effectiveness of decisions related to financial issues.

7. Sustainability: The benefit to the environment through design.

8. Response to Client and User needs: Additional benefits interpreted from the brief, serving the client or users and the community.

The assessment criteria demonstrate the balance of issues under consideration by juries. In summary,for a work of architecture to be worthy of a national award it has to satisfy criteria that generally cover the response to a brief with clarity of expression in the architectural concept as well as outcomes defined by some measure of public good.

The awards when announced attract national and local media attention. Interest in the annual results is broadly based with extensive print and television media coverage.[7]This is an indication that the awards program engages many Australians with architecture judged by the profession to be of the highest standard in the nation. The assessment criteria concerned with questions of public benefit focus the engagement of the media on issues of relevance to the community.Most importantly the reputation of the program for assessment processes that have demonstrable rigor,independence and integrity underpins acceptance and influence in the community of RAIA awarded architecture. The annual recognition and public debate of awarded architecture is, arguably, a significant contribution by the RAIA to the awareness of the value of the profession to the Australian community.

Significant RAIA Public and Commercial Architecture Awards, 2007-2009

The RAIA Sir Zelman Cowen Award[8]is considered the most prestigious award for public architecture in Australia, commonly described as the ‘name’award in this category. The RAIA Harry Seidler Award[9]is the equivalent‘name’award in the category of Commercial Architecture. Only one name award can be given in any one year in each category although there are theoretically no limits to the number of general awards that a jury can bestow in each category.[10]Typically, there are a small total number of awards given in each category annually.

Each of the following buildings are selected from the national award program in the Public and Commercial Architecture categories[11]of 2007, 2008 and 2009 for the purpose of exploring their impact on Australian design culture.

State Library of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland

The 2007 Sir Zelman Cowan national award for Public Architecture went to the State Library of Queensland designed by Donovan Hill Architects (in association with Peddle Thorp Architects). An important objective of the brief was to substantially increase the socio-demographic range and level of use of the library to develop the cultural value of public facilities in the community.

The architects have responded with provocative,engaging and assertive architecture. The dramatic exterior forms, and use of colour dominates the principal approach and river views delivering a memorable inversion of the more conventional and restrained architecture typical of public libraries.

The interiors for Donovan Hill are likened to the making of a‘miniature city’with routes to various specialized functions punctuated by views out and arranged through a matrix of differentiated spatial and material experiences designed to maximize the enjoyment of the user.

This is not a library that asserts through the architecture the authority of the librarian and role of learning in society. Instead it conveys a spirit of open enquiry, flexible learning pathways and a social hub for accessing information using contemporary technology and ways of learning.

The jury citation refers to the architecture’s“vast ambition to demand and excite public engagement.”[12]This ambition accords with the common objective to increase public awareness and use of government library facilities throughout Australia. In this sense, Donovan Hill has explored a new design paradigm for major public library architecture as the vehicle to broaden the role of libraries in the community.

Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA), Brisbane, Queensland

Adjacent to the State Library of Queensland is the new Gallery of Modern Art designed by Architectus,an awarded building in the same year as the State Library of Queensland. These buildings form part of the Queensland Cultural Centre precinct with other distinguished architecture that includes the Queensland Art Gallery of 1982, designed by Robin Gibson and Partners.

The exterior form of GoMA is dominated by a substantial cantilevered roof structure designed to shade the walls of the building to significantly reduce heat load. The roof form is detailed to dramatize the cantilever, emphasizing a sense of lightness, perhaps inspired by the culture of local architecture and derived, from statements by the architects, from a consideration of the climatic conditions of Queensland.

The concerns to achieve appropriate visitor experiences for the art and clarity of public circulation determined the organizational design principles. A sequence of interconnected gallery spaces emphasizing the use of natural daylight and voids defines the spatial experience and interior character.

GoMA further contributes to the development of the precinct by permitting access from three distinct public open spaces. The architecture aims to be perceived as a pavilion form, integrated with and supporting adjacent public open space uses to enhance its value as a public amenity for the city.[13]

Investment in architecture by government for major cultural facilities has been an essential element of Australia’s cultural and economic development.Government acting as the commissioning agent has not always undertaken this role without significant issues emerging that have threatened the quality of the architecture in the construction process. The RAIA actively supported the architects responsible for both GoMA and the State Library of Queensland over concerns related to maintaining design integrity during the construction process.[14]

The Cherrell Hirst Creative Learning Centre, Brisbane Grammar School, Brisbane, Queensland

In 2008 the coveted Sir Zelman Cowan award was once again taken out by Brisbane and Queensland architects, this time by the firm, m3architecutre. The awarded building is a new learning facility commissioned by Brisbane Grammar School-a private secondary school for the education of young women.

The brief required facilities for art, music, drama and technology in a single ‘creative arts’building. The architecture derived from the school’s direction to explore physical environments to encourage user-determined educational experiences. In effect the architecture is organized around two distinct elements to support structured and unstructured learning experiences for students. The structured learning spaces are over six levels and contain the facilities for formal teaching and learning including classrooms and purpose designed kitchen/tuck shop, art, and music and drama spaces. The unstructured learning spaces are adjacent, placed to be vertically integrated under a major extension of the roof to provide protection from the elements. The resultant informal spaces support a new social environment to encourage unstructured, collaborative learning and the development of independent thinking-a fundamental tenet of creative practice required by the teaching philosophy of the school.

17 休姆市政厅办公楼街道外景/Hume City Council,exterior street view(摄影/Photo: John Gollings)

18 休姆市政厅办公楼标准层平面/Hume City Council,typical upper level plan(Lyons)

19 摩纳哥领事馆街道景观/Monaco House, street view

20 摩纳哥领事馆内景/Monaco House, interior view(19.20摄影/Photo: Trevor Mein)

Approximately half of the volume of the building is, as a consequence, dedicated to a new type of social learning experience and environment. The architecture is memorable for the multilevel, informally structured,covered open space, designed without a specific functional program except to support circulation to the main enclosed and adjacent functional spaces.

Brisbane Grammar School’s teaching and learning objectives in the creative arts has inspired a new type of architectural space. The client brief has boldly employed architecture to facilitate innovative educational practices. The substantial covered area is an essential part of the school’s pedagogy-the provision of space for informal teaching and learning experiences between students, initiated through student social interaction.

The architects also developed other distinctive,expressive elements to reflect site conditions. For example, the major connection between the campus and the new building is directly through the new informal space. The progressively changing geometry of the concrete structure creates a dynamic character to dramatize the experience of the principal circulation axis of the campus. On the opposite side, terminating long vistas from a major road and sport fields, the architecture presents as a screen with optical properties to create a visual paradox and another dynamic expressive element as a representation of the school to the public.

From an environmental management perspective,the architecture integrates on-site grey water recycling and a range of related energy saving and waste minimization technologies.

The jury citation describes the architecture as‘directly detailed, well thought out and robust. It conveys a“no-nonsense”message-a bold and purposeful architecture that is heartening to contemplate when considering the education of young women.‘[15]

The awarding of this project has permitted a wider appreciation of the value that architecture can bring to achieving educational objectives. A new space to enhance opportunity for unstructured learning by capturing the social dimensions of the student experience is innovative and may lead to applications in the design of other secondary schools in Australia.A significant measure of a broader acceptance of this educational and architectural concept will be its integration into space standards required by government for secondary school facilities in Australia.

Nigel Peck Centre for Learning and Leadership,Melbourne Grammar School, Melbourne, Victoria

In the same year, in 2008, an award was given to another private school, Melbourne Grammar’s Nigel Peck Centre for Learning and Leadership designed by John Wardle Architect.

The architecture provides an exceptional enhancement of the public domain, whether experienced from the busy adjacent street or the publically accessible recreational space linking other buildings on the school campus. The form seems to continuously evolve using unique glazing and masonry details to invite engagement and delight with the architecture.

The interior facilities are casually arranged encouraging informal learning and social interaction between students. They appear to be generously appointed with high levels of natural light designed to reinforce the spatial qualities of the architecture. The interior and exterior architecture provide a compelling school learning environment-one that seems to encourage a sense of well being from students and staff evidenced by the enthusiastic comments of support for the achievements of the architect.

Climate control is an important design consideration with exceptional levels of solar access available to compensate heat loss during the winter months. Summer heat load is managed in part, by taking advantage of the reduction in student numbers requiring access during the extended summer school holiday period.

Requirements that support the skillful manipulation of the physical characteristics of architecture to enhance teaching and learning experiences through the imaginative use of space,light, material and form are absent from government guidelines for the design of secondary schools.Government secondary school design guidelines do not emphasize the integration of informal and structured learning spaces. The physical environments of standard school buildings in Australia commissioned by government do not yet typically involve the types of spaces or architectural responses evident in the Nigel Peck Centre for Learning and Leadership.

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory

In 2009 the Sir Zelman Cowan award was given to the National Portrait Gallery by the Sydney based architects Johnson Pilton Walker.

The location of the Portrait Gallery is within the Parliamentary Triangle of Canberra, adjacent to the substantial and highly awarded architecture of Edwards Madigan Torzillo and Briggs, being the National Gallery(1982) and the High Court of Australia (1980). The National Portrait Gallery is low by comparison to its neighbours, highlighting the landscape setting including views from the interior. The horizontal form of the architecture is emphasized by a dramatic cantilevered structure at the entry creating a striking counterpoint to the scale and verticality of the significantly larger Edwards Madigan Torzillo and Briggs works nearby.

The interior is carefully calibrated to establish an intimate scale to a series of interlocking spaces well suited to the experience of viewing portrait art. The interior character is formed directly from the materials and structure of the architecture, enhanced by diffuse natural light in all galleries, thereby also minimizing the use of artificial light. The visitor is led through a series of linear galleries guided by natural light and structure. The architects also state that spatial concepts were developed taking into account an understanding of the proportions of the human face derived from the Golden Section or Fibonacci Series in mathematics. The interior architecture is calming in effect, slowing the visitors pace appropriately for the contemplation of portraiture.

Concerns about the placement of art in architecture and consideration of the human experience in contemplating art provide a refreshing focus for the architecture of this building type. The jury citation notes reference to the precedent of Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Museum (1972) to guide the interpretation of the architectural concept.[16]This is in contrast to the recent tendency to use the Frank Lloyd Wright’s original Guggenheim Museum as a typology characterized by the employment of a dramatic central space and peripheral gallery display areas to organize the spatial experience.

The jury citation also indicates criticism of government for not providing sufficient funding to deliver an appropriately sized facility, given the level of significance and popularity of the collection. The inappropriate level of support by government for the architecture of cultural facilities is also an issue previously identified in the 2007 awarded cultural projects.

All Saints Primary School, Sydney, New South Wales

In the same year as the National Portrait Gallery an award was given to a privately commissioned primary school associated with the Greek Orthodox Church in Australia, designed by Candalepas Associates from Sydney.

Unlike both the previous awarded schools from 2008 this work is clearly conceived within the constraints of a lower budget. Notwithstanding the budget, the school life of the student and staff is enriched with an extraordinarily expressive and engaging architecture that enhances the experience of the relatively conventional teaching spaces.

21 新阿克顿东楼外景/New Acton East, exterior view

22 新阿克顿东楼内景/New Acton East, interior view(21.22摄影/Photo: Dianna Snape)

23 常青藤夜总会中庭/Ivy, atrium

24 常青藤夜总会乔治大街景观/Ivy, view from George Street(23.24摄影/Photo: Trevor Mein)

The design arranges basic classrooms connected over four levels by continuous walkways with outlook available to the playground and the rest of the campus across a street. It is the skillful use of masonry and infill elements that provides an immediate and positive impact on approach and continues to suggest a playful experiential dimension when moving around the spaces that are otherwise straightforward in arrangement.

The jury citation[17]again alludes to the value of this work as a guide to how government funded school architecture can be improved. Reference is made to the failures of recently completed government school projects to achieve reasonable levels of architectural design and to address site-specific considerations adequately, relying instead on standard templates for the layout and three-dimensional arrangement of the architecture.

Eureka Tower, Melbourne, Victoria

Eureka Tower, designed by Fender Katsalidis Architects, was the 2007 recipient of the RAIA Harry Seidler National Award for Commercial Architecture.The architecture accommodates a complex range of uses-apartments, tourist facilities, function rooms,a hotel and show rooms-in over 80 levels of development. The range of functions reflects a relatively recent type of urban building in Australia,commonly referred to as a ‘mixed-use’development.With notable exceptions, the work of Harry Seidler &Associates being one, high-rise architecture in Australia has historically delivered generally adequate building stock but little to encourage engagement at a cultural level by the general public and the architectural profession including historians of architecture.

Eureka Tower is an example of high-rise architecture that has captured the imagination of the general public and now is one of the important icons for the city of Melbourne. The architecture of Eureka Tower contributes positively to the character of the city through its dramatic form and slender proportions,particularly when viewed from the north and south.The use of colour and glass define the exterior character providing distinctive reflective effects throughout the day.

Australian cities are generally of low density with high-rise residential architecture not commonly accepted as a desirable development type. Eureka Tower has been immediately accepted as significant architecture in the Melbourne central urban area contributing to greater public acceptance of this form of residential development. The acceptance of Eureka Tower as an example of denser residential typologies is significant for reasons that include the need to contribute through architecture to lowering the national carbon footprint.

Riparian Plaza, Brisbane, Queensland

Awarded in the same year and category as the Eureka Tower, Riparian Plaza designed by Harry Seidler& Associates is another exemplar of the mixed-use high rise building type, this time with a car park below offices and topped by apartments. The ground level is conceived as an extension of the pedestrian environment minimizing built area and planned to separate commercial and residential entry points.

Unlike Eureka, each function is differentiated by the external treatment of the architecture. The masonry forms and fenestration change to reflect each use resulting in a complex architectural treatment that is immediately recognizable at any distance. This ensures the architecture becomes a landmark in the city skyline.

Riparian Plaza is a consummate work of the architect adding to an already rich legacy, a new palette of inventive masonry architectural forms.Riparian Plaza reflects the evolving development of the use of concrete as the principal material for high rise architecture in Australia.

Hume City Council Offices, Hume, Victoria

Suburban centres in Australia often do not provide many examples of fine contemporary commercial architecture. Yet in 2008 the Harry Seidler award was given to the architect Lyons, for Hume City Offices[18]-a six level office building sited next to a shopping mall car park, near a freeway and railway station.

The architecture is deliberately bold with its form, colour and active ground uses enriching an otherwise relatively bland urban environment. Office workers and visitors are made immediately aware of the positive value of architecture and an improved public domain for the town centre. The interiors are planned around the sculpted external form to provide memorable circulation and stimulating working environments. The architecture also integrates advanced energy efficient design and technology as part of the commitment by the client to achieving more sustainable urban environments.

The Hume City Council aimed to demonstrate through architecture a forward thinking approach to commercial development within the typical constraints of Local Government budgets. The outcome is an exemplar of how architecture can effectively improve urban environments by making more sustainable, culturally valued regional centres. This project demonstrates leadership through a considered project specific brief,developed and implemented by government.

Monaco House, Melbourne, Victoria

In the same year as the Hume City Offices, a small Melbourne city lot on a lane was also awarded. Monaco House is a bespoke office by the architect McBride Charles Ryan. Both the interior and exterior are conceived as a visual essay in folded, complex geometry enlivening the experience for both users and pedestrians in the lane it addresses.

Visual puns alluding to the consular function enrich the reading of the architecture. These include a projecting elevated balcony for one person that implies an honorific function to address people on the lane and a minuscule grassed area at ground level symbolizing, perhaps, the Municipality of Monaco. In other respects the architecture is straightforward with a small core located to maximize interior space. The lasting contribution of the architecture is the enrichment of the public domain through the mastery of form and material to deliver an experience of extraordinary visual interest.

New Acton East, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory

In 2008, another award in the commercial category was given to Fender Katsalidis Architects for New Acton East, a mixed-use development over eight levels comprising of retail space, offices and apartments.

The ground level pedestrian experience evolves from a sensitive integration of historic building fabric and new elements designed around courtyard and wide circulation pathways. Contemporary art specifically commissioned and integrated with the architecture contributes to the experience of visitors and residents. The art enriches otherwise deeper interior circulation paths linking major foyer entry points to retail activity. The form of the architecture is partly derived from the varying interior uses and specific site characteristics including view opportunities for upper level apartments.

In a city with abundant landscape often poorly conceived when its adjacent urban buildings are usually set back from the street alignment, resulting in the failure of forming readable street space, New Acton East is refreshing to experience. As a consequence,this building strengthens the urban character of the public space and provides a new urban paradigm for commercial architecture in Canberra.

Ivy, Sydney, New South Wales

In 2009 Ivy, designed by Woods Bagot Architects in collaboration with Merivale Group and Hecker Phelan Gutherie Interior Designers, received the Harry Seidler Award. The jury citation described the development as “part Roman baths, part smart restaurants, part urbane gathering place.”[19]

Ivy is Sydney’s most substantial example of architecture of entertainment, hospitality and in a sense, fantasy-a meeting place for a predominantly younger market and with restaurants, ballrooms,rooftop swimming pools and discrete cabanas to appeal to all generations.

In Australia, architecture for this building type is of a generally poor standard, relying on the simplest form of enclosure to provide space for decorated interior functions. Examples include the many sporting club structures, venues for weddings and other forms of entertainment or places for gambling. Ivy breaks from this prosaic approach using architecture to substantially improve the public domain by creating new uses in the formerly blighted rear lane. The architectural expression on George Street, one of Sydney’s most historic streets, reflects the optimistic purpose of the enterprise.

The resultant national award is rare for this building type. This perhaps reflects that never before in Australia, has an entertainment venue of this scalebeen built with commitment to urban design,architecture and interior design of substance.

Impact of awards on Australian design culture

Awarded architecture is nationally publicized engaging broad public debate. Awarded architecture affects the daily lives of the users and visitors to each work, as the significance of each award is prized and communicated to be of cultural value. The publicity enhances the careers and influence of successful architects. The profession also generally benefits from the exposure with recognition for culturally valued architecture clearly understood by the public as an aspiration commonly shared by architects.

The RAIA mission, as previously noted, aims to‘advance the interests of members, their professional standards and contemporary practice; and to expand and advocate the values of architects and architecture to the sustainable growth of our community, economy and culture.’The award program clearly aligns with these objectives by maintaining credible standards of assessment with transparent selection processes and by having as jury members a substantial proportion of practicing architects.

From the case studies, it is noted that recent awarded secondary schools have been funded by private enterprises even though the majority of construction for this building type is undertaken through government funding and management processes. The absence of any government funded school from the award program over three years indicates a strong divergence in the standards of architecture between the public and private school sectors.

Government at national and state levels is well represented in the awards for major cultural infrastructure with accompanying testimony from the profession that the methods of procurement and implementation need reform, to more fairly reflect the complexity of the design and construction tasks of this building type. At Local Government level, the award to a regional commercial office provides encouragement to support architectural excellence integrated with urban improvements and advanced environmental design initiatives.

Regional considerations are evident in some awarded works highlighting varying conditions of practice, site-specific design issues and the cultural context influencing the design focus of local architects.GoMA in Brisbane and Monaco House in Melbourne are examples of architecture that in part are derived from cultural influences reflected in local academic institutions often guided by influential architectural personalities.

RAIA award program contributes positively to the development of architecture in Australia. The program has a high participation rate from the profession and generates considerable public interest. Awarded architecture becomes valued in local communities influencing generations of future clients and policy makers responsible for the stewardship of the built environment. □ (All images courtesy: The Australian Institute of Architects’ Architecture Awards)

注释/Notes:

[1]The RAIA was formed in 1930 and currently has almost 10,000 members in Australia and internationally.See The Australian Institute of Architects, “Mission Statement”(2010), http://www.architecture.com.au/i-cms?page=165 (accessed 16 April 2010).

[2]Ibid.

[3]Australian Institute of Architects,2010 Awards Jurors Handbook(2010), http://www.architecture.com.au/icms_file?page=13650/2010_Awards_Jury_Handbook.pdf(accessed 10 August 2010). The handbook also describes the program in more detail including the RAIA award policy review of 2005/6.

[4]For a full description of the mechanisms to achieve an integrated, hierarchical awards program, see ibid.,4: “Awards Structure.”

[5]Ibid., 2.1: “Aims.”

[6]Ibid., 7.2: “Core Evaluation Criteria.”

[7]Specific data from the RAIA quantifying media coverage is unavailable. Typically, national print media coverage includes a major article in a colour magazine and occasional national TV coverage on specific buildings. Local print and media coverage focuses on successful outcomes from the relevant local area. The professional journal,Architecture Australia, devotes one particular issue on the national awards annually.

[8]Named after a distinguished Australian citizen,former Governor General and supporter of architecture and architects. Architecture in this award category must be predominantly of a public or institutional nature and require compliance within class 9 of theBuilding Code of Australia(BCA). See Australian Institute of Architects,2010 Awards Entry Handbook, 6.2: “Categories”(2010),http://www.architecture.com.au/i-cms?page=1.13262.13475.1195 (accessed 10 August 2010).

[9]Named after one of Australia’s most prominent architects of the modern era known for exceptional commercial and residential architecture. Architecture in this category must be built primarily for commercial purposes, generally falling within theBCAclasses 3b,5, 6, 7 and 8. See ibid.

[10]For other ‘name’awards for different building types (e.g. residential architecture), see ibid. But they are not the subject of this discussion.

[11]There are eleven main national RAIA award categories being: Public Architecture; Residential Architecture-Houses; Residential Architecture-Multiple Housing; Heritage; Commercial Architecture;Interior Architecture; Urban Design; Small Project Architecture; Sustainable Architecture; 25 Year Award for Enduring Architecture; and International Architecture. See ibid.

[12]“2007 RAIA national Architecture Awards,”Architecture Australia96, no. 6 (2007), http://www.architecturemedia.com/aa/aaissue.php?issueid=200711 (accessed 9 August 2010).

[13]Ibid.

[14]Error! Reference source not found. (CEO of the RAIA), personal communication with the author, 9 August 2010.

[15]“2007 RAIA national Architecture Awards.”

[16]“Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Architecture,”Architecture Australia98, no. 6 (2009),http://www.architecturemedia.com/aa/aaissue.php?issueid=200911 (accessed 9 August 2010).

[17]“National Award for Public Architecture,”Architecture Australia98, no. 6.

[18]“Harry Seidler Award for Commercial Architecture,”Architecture Australia97, no. 6: (2008),http://www.architecturemedia.com/aa/aaissue.php?issueid=200811 (accessed August 9, 2010).

[19]“Harry Seidler Award for Commercial Architecture,”Architecture Australia98, no. 6 (2009),http://www.architecturemedia.com/aa/aaissue.php?issueid=200911 (accessed 9 August 9 2010).