Treasures Abroad

2010-03-15

Nowadays, more and more Chinese people are able to afford travel overseas. During their journeys, museums are a must-see, where they not only appreciate foreign art, but also fi nd numerous Chinese cultural relics that they have never seen in China. What has astonished them very often is that so many Chinese cultural relics are well collected in these foreign museums.

Beijing Review reporters Chen Wen and Zan Jifang recently interviewed staff at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Harvard Art Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston, to get a general picture what has happened to China’s cultural relics overseas. Here are excerpts from the interviews:

When did your museum start to collect Chinese art and relics? What are the major sources of this collection?

Elinor Pearlstein, Art Institute of Chicago:

The department itself was founded in 1922. The earliest pieces acquired, some of them, were collected by one woman, Ms.Calhoun, whose husband used to serve as U.S. ambassador to China. They lived right outside the Forbidden City between 1909 and 1913. We have some of her letters here,which show she seemed to have purchased textiles from people who came to the U.S.Embassy to sell them. We also have a painting that was given to her by Empress Dowager Longyu (1868-1913) of the Qing Dynasty. Many Chicagoans had direct relationships with China, and she was the earliest.

Robert D. Mowry, Harvard Art Museum:

The first Chinese works of art were acquired in 1919 at the behest of Hervey Wetzel, a Harvard graduate who, by terms of his will, left portions of his collection to Harvard and also to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The works of art in the Wetzel collection were culturally and chronologically diverse, ranging from Italian Renaissance paintings, Chinese bronze ritual vessels to Korean ceramics and many others.

Kelly Gifford, Museum of Fine Arts(MFA), Boston:

How many pieces of Chinese relics does your museum have right now? How many of them are permanent and how many are for one-time exhibition only?

Elinor Pearlstein:

There are approximately 3,500 Chinese art pieces in our museum. Most of them are ceramics, around 2,000 pieces, maybe more.We have around 900 pieces of jade, most of which were collected by one American person, who died in 1935. We have 70 ancient bronzes, most of which were here in Chicago before World War II. Many of the pieces were given to the museum after the owners died. We have around 150 paintings. Of decorative art, together we have about 100 pieces, including furniture, lacquer and silver objects.

Most of the pieces were donated. We also have bought objects, which donors paid for. All the pieces are in the permanent collection of the museum.

Robert D. Mowry:

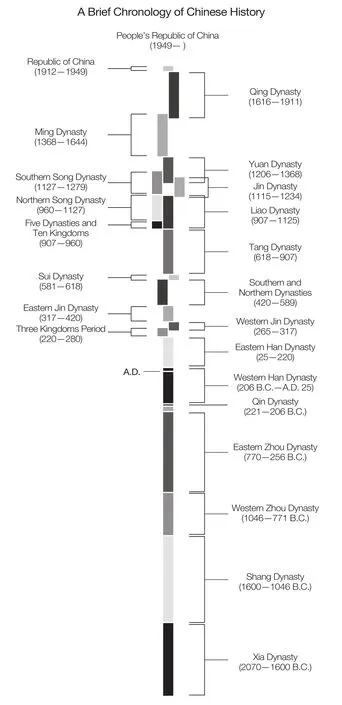

We have 6,466 Chinese art pieces. That includes 1,715 ceramics (including 1,275 vessels, 259 collected shards and 222 ceramic sculptures/tomb fi gurines), 856 jades of the Neolithic Age and Shang (1600-1046 B.C.), Zhou (11th century-771 B.C.),Song (960-1279), Yuan (1271-1368), Ming(1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, 1,127 paintings and calligraphy pieces(both traditional and modern/contemporary), 920 printed materials (including printed books and scrolls and numerous so-called New Year’s prints) and 1,848 ancient ritual bronzes, Buddhist sculptures,rhinoceros horn carvings, lacquers, textiles and others.

Virtually all of the pieces listed above are part of the permanent collection. They are not loans for temporary exhibition or study.

Kelly Gifford:

The MFA has approximately 8,000 objects in the Chinese collection, including paintings, sculptures, textiles, ceramics, metalwork and decorative arts.

The majority of works are part of the museum’s collection.

What genres are the major collections of Chinese art and relics in your museum?What is the most precious part of your collection of Chinese relics?

Elinor Pearlstein:

The largest collection is ceramics. We have a very strong collection of Tang (618-907) ceramics, including burial materials.And we also have a large collection of Song ceramics. Most of the ceramic pieces in later periods are in storage. We have a very good collection of the Qing Dynasty, most are from the Emperor Yongzheng (1678-1735)period. As we have very limited space to show them, we rotate them from period to period.

The jade pieces are ancient. We have pieces from Neolithic and prehistoric periods and Shang, Zhou and Han (202 B.C.-A.D.220) dynasties.

We have very unusual bronzes. For example, we have a large bronze vessel with a long inscription. There is also a round wine

vessel, with gold and silver painted on it and

the design is a dragon. Dating to the Han Dynasty, this piece came to the museum in 1927.

Of sculptures, we have two heads of Buddhist fi gures dating to the Northern Song Dynasty. They are very rare because the material is very delicate. When scholars from China came here, they often told us that they had never seen it before. The material is so delicate that not many pieces survived. The heads are hollow, and if you lift them, the weight is very little.

We also have very good tomb figures.We have many important pieces of Dingyao,early white porcelain. We also have Qingbaiyao porcelains, or bluish white. Of the jades, we have many beautiful pendants that date to the Late Zhou Dynasty and the Warring States Period.

Robert D. Mowry:

The most important Chinese holdings are archaic jades (from the Neolithic period through Shang and Zhou dynasties), bronze ritual vessels (Shang, Zhou and Han dynasties), Buddhist sculptures (both gilt bronze and stone dating to Northern Wei through Song dynasties), Chinese ceramics (from the Neolithic period through the Qing Dynasty), rhinoceros-horn carvings (in the Ming and Qing dynasties), and modern and contemporary ink paintings.

Kelly Gifford:

The major collection of our museum is early figure and landscape paintings,Buddhist sculptures, ceramics and porcelain.

Approximately, how many visitors came to see the Chinese section in your museum every year?

Elinor Pearlstein:

About 3.3 million visitors come to the museum a year. We do not keep a record of the number of people who go to each gallery.

Robert D. Mowry:

Perhaps 60,000 people see our displays of Chinese art each year. They are impressed by the displays, particularly since we have explanatory labels, and we offer tours, lectures and symposia.

Kelly Gifford:

The MFA welcomes approximately 1 million visitors a year.

Who wrote the captions and illustrations for those art pieces? How and where did you get the background information?

Elinor Pearlstein:

I write the most of the gallery labels.There was a curator who was an expert in ceramics. He wrote most ceramics labels.

Robert D. Mowry:

The works of art have been cataloged by the museum’s curatorial staff who are trained specialists and they have particular knowledge about the objects. The museum’s curators have also written the labels for the pieces on display, just as they have written the scholarly catalogs that accompany the museum’s exhibitions.

Kelly Gifford:

Curators and researchers in the department wrote the captions. The related information is acquired from purchase records, correspondence letters between collectors and curators and primary and secondary published materials.

Besides exhibition, are the Chinese relics used for other purposes, such as research and education?

Elinor Pearlstein:

We have a very large education department,and we work closely with them. We have a center for teachers, called the Teacher Resource Center. We sometimes write brochures for them. We also have very good education staff.We lecture to community groups, either in the museum or go to their places. We also hold seminars on Chinese relics. College and high school students can work as interns in our department or the education department.

Robert D. Mowry:

With a large and important collection,nearly all of the works in the collection of the Harvard Art Museum are used for research and teaching, in keeping with the museum’s mission. In fact, Harvard has been a leader over the decades in teaching with original works of art.

Kelly Gifford:

The MFA is committed to making the collections accessible. We have seen major increases in scholarly visits and requests for further information from the public as a direct result of more reliable and betterorganized information on the collection available online. The department also has an excellent publishing record in terms of exhibition catalogs. We are presently writing a Chinese highlights catalogue featuring 100 masterpieces.

What preservation measures does your museum use?

Elinor Pearlstein:

We have a conservation department with about 20 people, including specialists in metal works, ceramics, textiles, books, prints and paintings. They monitor the relics and control the displays’ temperature and humidity.

Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk, handscroll, Northern Song Dynasty, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

If we need to send some of our collection to other museums for special exhibitions, our curators must first determine the pieces are safe to travel. If there is a problem with their condition, we will not allow it.

Robert D. Mowry:

Works of art are stored carefully where the temperature and humidity are controlled.Since different types of materials have differing optimum temperature/humidity requirements for long-term preservation, we are able to adjust the climatic conditions in our storerooms to make the conditions as suitable as possible for long-term preservation of the pieces. The shelves for storing the pieces are lined so that they can well protect them; in addition, padding is placed between the pieces so that they cannot touch each other while on the shelves. The storage cabinets and the storerooms also offer protection from seismic activity.

In addition, the Harvard Art Museum has a large, well-developed conservation laboratory. The Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies is one of the world’s leading fi ne arts laboratories for conservation treatment, science and training. The conservators monitor the works in the collection,both in storage and on display, and they treat any works needing attention. It might be noted modern conservation treatment procedures and modern conservation analytic science were developed at the Harvard Art Museum, beginning in the 1920s.

Kelly Gifford:

The MFA established an Asian conservation studio in 1907-13 as part of the Department of Chinese and Japanese Art.Today we have five full-time conservators,who work on our Asian painting and print collection. In order to preserve the objects and paintings, the museum abides by very strict standards of conservation. Objects are stored in climate-controlled environments where light levels, humidity and vibrations are closely monitored. Paintings are displayed for only nine months at a time.Handling of objects is kept to a minimum.

Is there any exchange and cooperation between your museum and museums in China?

Elinor Pearlstein:

Yes. We have a scientist here now from the Forbidden City Museum. He is a scientist and is here for six months. He is working primarily in our conservation laboratory. We have curators here from different Chinese museums. The University of Chicago has one of the best programs in the United States in Chinese studies and Chinese history.Very often, the university has programs, in which archaeologists and historians coming from China take part. Chinese experts and scholars also visit our museum very often,and we continue to stay in touch with them.For example, now the university is planning a seminar on bronze inscriptions. They have invited scholars from Peking University and Shanghai Museum.

Prehistoric Period(before 21st century B.C.)

Robert D. Mowry:

Although our museum does not have formal cooperative arrangements with museums in China, curators from the Harvard Art Museum visit China virtually every year and they have close relations with their colleagues in museums and archaeological bureaus (including archaeological sites)throughout China. In addition, numerous scholars from China visit our museum each year, some coming to study works in the collection, others to study our display and conservation techniques, and others to spend a semester or a year at Harvard for research,using resources in our museum and in other Harvard museums and our many libraries.

Kelly Gifford:

We host many visits from Chinese museum colleagues and scholars, including recent visits from the Palace Museum (Beijing), the Hunan Provincial Museum and the Shanghai Museum. We are currently collaborating with the J.S. Lee Memorial Fellowship Program based in Hong Kong. ■

Collections Overseas

Head of a Luohan (Buddhist figure), Hollow dry lacquer,Northern Song, Liao, or Jin dynasties, Art Institute of Chicago

Foliate Flower Pot and Basin of Ming Dynasty, Harvard Art Museum

Arched Dragon Pendant, Jade, Eastern Zhou Dynasty,Warring States period, Art Institute of Chicago