Remembering Beijing’s Moat System

2009-09-23HUOJIANYING

HUO JIANYING

OVER the course of almost a millennium, Beijing served as the capital of four dynasties: the Jin (ruled by the Jurchens, 1115-1234), Yuan (the Mongol empire, 1271-1368), Ming (ruled by the Han Chinese, 1368-1644) and Qing (Manchu rule, 1644-1911). On any map of dynastic Beijing, one finds a blue line of water defining the citys outline– the square “Central Capital” of the Jin, the rectangular “Big Capital” of the Yuan and the T-shaped “Northern Capital” (Bei Jing) of the Ming and Qing dynasties. No matter how the city boundaries shifted from dynasty to dynasty, a blue-lined moat always traced the capitals edge. The moats name has also remained constant throughout the centuries, literarily meaning “City-protecting River.” A moat girding a walled city was typical of ancient Chinese urban construction, serving defensive purposes, as well as providing a water supply and drain.

Inner and Outer Moats

Beijings moat system was more complicated than those of other Chinese cities, as it comprised outer, inner and imperial moats. The Ming and Qing capital was encircled by four sets of walls, dividing the city into outer, inner, imperial and palatial (Forbidden City) sections, each of which had a moat. Only some sections of this system can still be seen today.

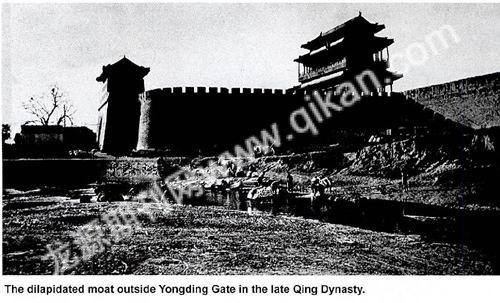

According to historical records, the outer and inner moats of the Ming Dynasty were 52 meters wide, five meters deep, and 20 meters from the foot of the city wall. Their vertical banks were formed by mortar-bonded granite blocks 50 centimeters thick and 70 centimeters across, topped at ground level by a low wall. Their moat beds were formed from rammed lime-earth. The two moats totaled about 41 kilometers in length.

The inner moat was dug when Emperor Yongle (reigned 1403-1424) rebuilt Beijing as the Ming capital. It roughly followed the course of the present-day Second Ring Road. The outer moat was an unfinished project launched by Emperor Jiajing (reigned 1521-1566). Since the Ming suffered frequent attacks by nomadic tribes, the emperor decided to build an outer city as a buffer zone. Construction started in 1550, but was soon suspended due to public resistance to mass destruction of civilian residences and shops. Construction resumed in 1553. According to the original plan, the outer wall would encompass the whole city and had 11 fortified gates and several water passes and sluice gates. Construction began in the south outside todays Zhengyangmen (Zhengyang Gate).

However, the project went no further as escalating frontier warfare and an accidental fire that damaged part of the Forbidden City forced the imperial court to concentrate its limited financial and material resources on national defense and reconstruction of the imperial palace. Seeing no other option, the cash-strapped builders extended the finished section of the scheduled outer city wall northward to join the inner wall, forming a rectangle and turning the shape of the walled city into the Chinese character 凸.

The main course of the outer moat, today known as the Southern Moat, is 22 to 45 meters wide and 15.5 kilometers long. It starts at Xibianmen and flows northward into the Tonghui River via Guangqumen, linking the Western Moat and Lotus River.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, Beijing had plenty of water, and its Western Hills were noted for more than 30 springs which fed into the city via Kunming Lake and the Changhe and Gaoliang rivers. According to a survey conducted by the municipal geological department in the 1950s, Beijing had 1,347 springs in total.

Water Passes

In the past, the rural and urban divide was clearly demarcated by Beijings moat at the foot of the city wall. Outside the moat was a pastoral scene of chequered fields coursed by willow-lined rivers and lakes.

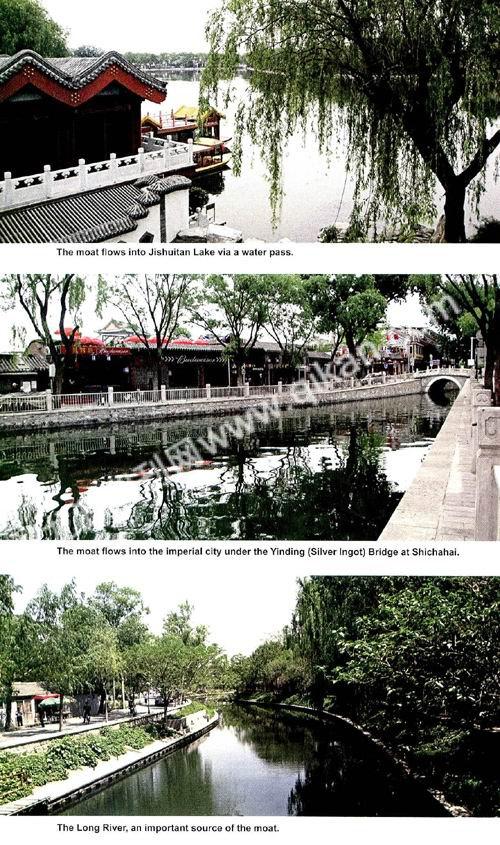

During the Yuan Dynasty, the area today known as Jishuitan in the citys north was the terminal of the Grand Canal from Hangzhou to Beijing. Its vast zone of waters perennially buzzed with cargo ships and was lined by various businesses. In the Ming Dynasty, the city wall and moat were built here, and Jishuitan was walled inside Deshengmen (Desheng Gate), shrinking its water surface considerably.

The area immediately outside the gate was called Shuiguan, or Water Pass, a tunnel beneath the city wall that allowed the moat to flow into the city. The pass through the outer city wall had a sluice gate to control the flow. The pass through the inner city wall was an arch built of stone slabs fenced by iron rails. Water roared through this arch, producing a thunderous noise and chilling the surrounding air. Opposite the arch was a stone stele carved with a ferocious-looking and grotesque Water Subduing Beast. The animal looked so horrible that few children dared to get close. The water pass was in the city wall west of Desheng Gate, demolished in the 1960s when the Second Ring Road and the subway were built.

The Northwestern Moat channeled water inside the city. It branched into two rivers after flowing in via the water pass west of Desheng Gate. One ran south into Jishuitan, Shichahai and Beihai lakes, and fed the Golden Water River of the imperial palace. The other followed the course of the moat, flowing southeastward into the Tonghui River via Andingmen, Dongzhimen, Chaoyangmen and Dongbianmen. The Tonghui River was built in the Yuan Dynasty to connect the Grand Canal and the inner city water system, and continued to be used until the early 20th century.

The old city wall of Beijing had 13 water passes, rounding out the citys water supply and drainage system. These were fenced by two or three iron rails and guarded by soldiers.

Imperial Moat

The moats girding the imperial and palatial sections of Beijing are known as the imperial moat. The former can hardly be seen today, but the latter – the one surrounding the Forbidden City – has survived almost completely intact.

The Imperial City directly skirting the Forbidden City was a special service zone for the imperial family. During the Ming and Qing dynasties it housed central government offices, a few imperial temples, and various departments taking care of imperial needs such as the Rice and Salt Warehouse, the Weaving and Dyeing Bureau, a porcelain warehouse and the Imperial Archive. After the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the Imperial City and its moat disappeared with reconstruction of the city. Today the only traces of the former area are some of the old place names.

A lane near todays Donghuangchenggen (Foot of the East Imperial City Wall) is named Qihelou, or River-straddling Tower, referring to a pavilion-style bridge built across the imperial moat during the Ming Dynasty. The lane has survived, but the bridge was gone by the late Qing Dynasty.

Similarly, Yinzha (Silver Sluice) Hutong west of Qihelou bends and turns like a winding river, as during the Yuan Dynasty the area was part of the imperial river system and became an imperial pasture in the Ming Dynasty. Other names in the vicinity also remind one of the imperial moat, such as Nanheyan (Southern River Edge), Beiheyan (Northern River Edge), Beihe (North River) Hutong and the Changpu River, which survives as a small body of water to this day.

The moat around the Forbidden City is also known as the Tongzi (Tube) River, and the section in front of Tianan Gate is called Jinshui (Golden Water) River. The moat – 52 meters wide, four meters deep and 3.5 kilometers long – was the first defensive line outside the imperial palace, and its banks are fortified with stone blocks. The banks and bed of the Inner Golden Water River inside the Forbidden City are built of white marble.

Like the moats outside the palace, the palatial moat had two functions: a defensive barrier and a water supply/drainage system. Two fires in the palace during the Ming Dynasty were put out using moat water, and palace reconstruction during the Qing Dynasty made use of the moat as well. The Qing imperial family also grew lotuses here. The roots supplied the imperial kitchen, while surplus plants were sold in markets outside.

Then and Now

Droughts have only plagued Beijing in recent decades. In fact, according to historical records in the 800 years from the Jin Dynasty to 1949, Beijings Yongding River flooded 104 times, including 68 times in the 268 years of the Qing Dynasty – an average of once every four years. However, the imperial capital was never inundated, thanks to the solid and effective moat system, which apart from defense and drainage functions, also provided a transport system and beautiful water scenery.

Unfortunately, the greater part of the old moat has been destroyed by urban expansion and construction. The most recent case was the disappearance of the moat built by Ming Emperor Yongle that ran past Xuanwumen, Qianmen and Chongwenmen. Locals nicknamed it the Qiansanmen (Front Three Gates) Moat. Before the Outer City was built, the Qiansanmen Moat was the southernmost defensive line of the Ming capital. Later, it became the only artificial river that traversed Beijing. Boats that carried grain supplies and imperial tributes from South China along the Grand Canal went into the city via the eastern section of the moat. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the moat was also a recreational area for local citizens, who skated on its ice in winter and floated river lanterns on the calm surface in summer. In 1965, the moat was turned into an underground river and vanished.

Things started to change in the 1980s, and by the 1990s renovation of the Forbidden City Moat had been completed and part of the Imperial City Moat restored. In 2002, the Plan to Protect Beijing as a Historic and Cultural City listed protection of the municipal water system as a special project for the first time. The objective is to renovate and protect Beijings water systems, so closely linked with the citys long history, then restore as many river sections of historic importance as possible. In the same year, the Changpu River was brought to light east of Tiananmen, as the concrete slabs and buildings covering it were removed. The restored section has now become a park.

A long-term restoration plan for the Qiansanmen Moat has also been drawn up. The current task is to curb real estate development in the area, and sometime in the future its many box-shaped residential buildings will be demolished, smoothing the way for the moats reemergence.