Work Worth Doing:From Honorable to Profitable

2009-09-23CHENSI

CHEN SI

THE social and economic evolution of China over thepast 60 years has brought many changes to how Chinese people view work, and the personal matter of selecting an occupation or calling. Initially, occupations fell into a kind of scale, rising from initial positions as workers and servicemen, to businessmen, entertainers and intellectuals.In more recent years, the social and technological advances of the new economy have increased the demand for skilled and creative work, new and transferred technical specialities, and emerging public service roles. A so-called “good job,” based on purely political and social factors, is a notion that has had to move over as Chinese people enjoy more freedom of choice. Multiple standards, including economic factors, now carve out the territory of work worth doing. Options in career paths have never been greater.

After the PRC was

founded, to be part of

the armed forces

became the dream of many young men.

Once Honorable Jobs

The working class became master of the country after the founding of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC), and non-rural workers increased rapidly. Two factors, stability of employment and high social status and earnings, made being a “worker,” especially one in a state-owned enterprise, simply the most sought-after occupation.

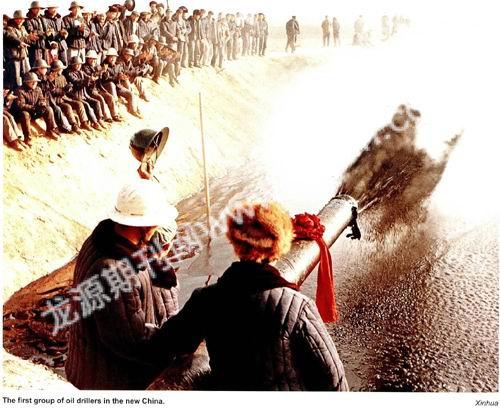

Industrial workers have been the backbone of the countrys enterprises, manifesting intense responsibility to their progress, and that of the country. Meng Tai from Angang Ironworks built the famous “Meng Tai Warehouse” by collecting thousands of scrapped parts that later played an important role in reconstructing Northeast China when the factory resumed its production during the Liberation War. As Chinas first group of oil workers, Wang Jinxi and his fellow workers drilled the first oil well in Daqing, Heilongjiang Province, ending Chinas oil-poor reputation and setting a world record of 100,000 meters drilled in one year.

Soldiers were looked down on in the old society, revealed by the saying, “Good iron doesnt make nails; true men dont make soldiers.” After the PRC was founded, to be part of the armed forces became the dream of many young men. “Who Is the Most Lovable,” an article on the heroism and revolutionary spirit of the Chinese Peoples Volunteers serving in the Korean War, influenced generations of Chinese people. Many excellent servicemen have become idols in their time. After being demobilized, military men and women enjoyed high social status, greater educational opportunities, andgreater latitude in career choice than others. Moreover, to marry an officer was many a girls dream then.

Cadre was also an admirable position. In times when ideology was paramount, to be an official was very popular, especially where political work held a cadre responsible for peoples ideological development. In years of material hardship, those professions that bridged people with relief in the form of grant coupons, or were engaged in food distribution, or put people close to leaders on a daily basis (such as a driver), were highly desirable.

Interestingly, the most hapless occupation was probably the intellectual. Before Chinas reform and opening-up in late 1978, they were satirized as “stinking ninth grade.” This label, given during the “cultural revolution” (1966-1976), stems from the 13th century when the Mongols ruled the country and the populace was sorted into ten social strata.The intellectual was superior only to the beggar and inferior even to a streetwalker. From 1966 to 1976, large numbers of intellectuals were transferred to do manual work in the countryside.

The Color of Money

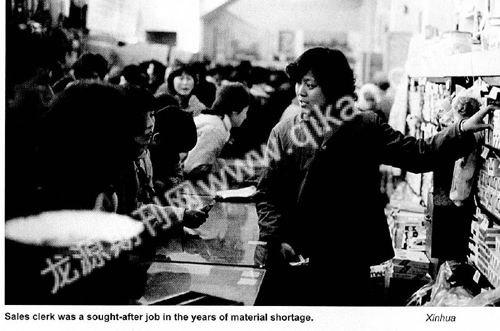

The reform and opening-up has been transforming the Chinese peoples concept of work over the past 30 years. The self-employed individual was the first to rock the boat. Engagement in commercial activities was hardly considered respectable at that time. Originally it was not even classified a proper job, only a recourse for marginal people who could not find decent and regular work. At first merchants or retailers could only be found on the street, some even obscuring their faces with a gauze mask for fear of being recognized by an acquaintance. Nevertheless, a handsome income soon made people hold them in higher esteem. At that time, the self-employed household was synonymous to a certain degree with an annual income of RMB 10,000, an enormous figure as the average workers monthly pay was less than RMB 100. Ridiculously, the earnings of scientists were a pitiful percentage of the individual proprietors income. Driven by economic interests, many people abandoned their regular job and “set sail in the commercial sea.” The number of self-employed individuals soared from one million in 1981 to 10 million in 1987.

Concepts like self-determination, job competition and unemployment have entered public discourse. A job was once something assigned by the government, an “iron rice bowl” of stable and lifelong employment where staff is closely linked to the work unit. Now employment is a means to make a living, and both the unit and employee can “fire” each other – conditions which ushered in the view that a job was an expression of ones interests, choices, and social identity. Rather than the most honorable job being the banner criterion, income and personal prospects have become the marks of veneration, especially if a high wage is attached to a popular profession.

In a 2007 survey jointly launched by the Social Research Center of China Youth Daily and the education channel of sohu.com, 2,723 respondents gave their opinion about the choice of ones first job.Some 80.8 percent valued “personal prospects” first, while 69.7 percent selected “well-paid.” Furthermore, student respondents expect themselves to be moneymakers at whatever they do. Wang Tingda, member of the National Committee of the Chinese Peoples Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), circulated a questionnaire this year probing 1,180 students in middle and primary school, and the youths identified “entrepreneur” as a top job, sharing the limelight only with singer and movie star.

The social status of the worker, by contrast, has fallen somehow. In 2007, a poll of 4,000 Shanghai households showed that only 1 percent is willing to be a common worker. After the reform of state-owned enterprises, tens of millions lost their jobs. According to China Labor Statistical Yearbook, China has laid off about 30 million workers over the years.

There are still signs answering to ones calling in life isnt entirely about making money.Fortunately, intellectuals have enjoyed more social respect recently. Mathematician Chen Jingrun and agronomist Yuan Longping were selected as national model workers. Chen Jingruns Chens Theorem has moved forwarduse of the Goldbach Conjecture. Yuan is known as the “father of hybrid rice,” whose research since the 1960s has helped China increase paddy production by over 50 billion kilograms from 1976 to 1987.

Even the work of the famous is assessed with new criteria. During the appraisal of nominees for 2005 national model workers, 30 entries from enterprises and sports circles were received, including Yao Ming (basketball star) and Liu Xiang (track and field champion), whose efforts for charity are widely known. A contribution to society, not just personal wealth creation, has become the focal criterion of the national model worker.

New Occupations

“Changes in social structure accelerate the subdivision of labor, and consequently create new occupations,” reckoned by Professor Xie Kang from the School of Business, Sun Yat-sen University. As the meal ticket of a lifetime, the “iron rice bowl” has been replaced by vocational choices of other kinds. Based on Chinas Occupational Classification, China recognizes nearly 2,000 occupations in its labor force and, since 2004, the Ministry of Labor and Social Security has defined and added new occupations several times a year. Those once indispensable jobs like knife grinder and pen mender have been pushed back on the stage of history. Typesetter and even paging operator, categories that emerged after reform and opening-up, subsequently disappeared along with their outdated technology.

Many of the new occupations are “grey-collar,” namely professional skilled personnel like animators, automobile tool and dye makers, and package designers, demanding a combination of both mental and physical work. The creative industry has also seen the rise of the fashion designer, exhibition stylist and landscape architect. Furthermore, careers like dietician, health and marriage consultant are gradually growing. Some vanished professions, such as auctioneer, are actually enjoying a comeback.

Guangdongs social changes are monitored in a four-year survey (2000-2004) undertaken jointly by the Department of Sociology and the Research Institute for Guangdong Development of Sun Yat-sen University. In 2000, it showed industrial workers and government functionaries were the largest occupational groups (making up 11.7 percent and 10.9 percent respectively), while in 2004, private entrepreneurs and the self-employed combined to form the biggest new occupational group (making up 12.9 percent and 11.1 percent respectively).The proportions of financial and commercial service personnel, company clerks, and foreign-funded enterprise employees also increased.Attitude probes indicate people still objectively identify social status with income. On the measure “greatest distinction between different social strata,” 45.1 percent selected “income,” and only 26.2 percent chose “quality of life” as the yardstick.However, few people approved of standards like “others esteem,” “knowledge level,” “life style” or “self satisfaction.” Moreover, 72.8 percent agreed that “consumption level indicates ones social stature and identity.”

According to Professor Li Weimin, the Department of Sociology, Sun Yat-sen University, the shift in how we measure and value work is part of atransformative social structure, where interests and values are diversified and their pursuit keeps society dynamic. People no longer classify themselves primarily by family or political background. Income level has become an important standard to judge ones social stratum in China, as well as a measure of the value of ones work and ones sense of belonging.

Rather than the most

honorable job being

the banner criterion,

income and personal

prospects have become

the marks of veneration.

There are still signs

answering to ones

calling in life isnt entirely about making money.

People no longer classify themselves primarily by family or political

background. Income level has become an important standard to judge ones

social stratum.